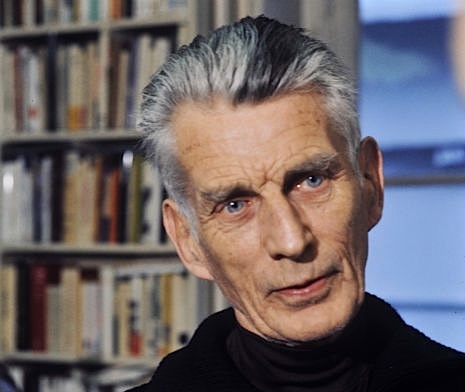

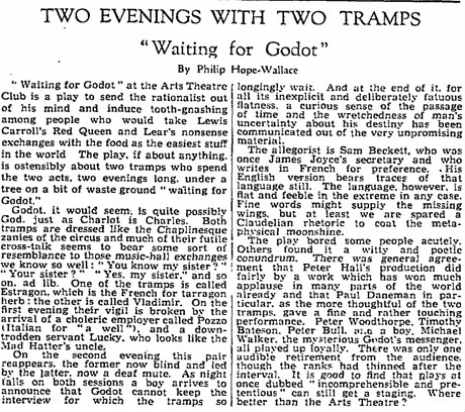

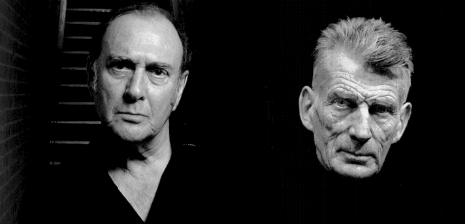

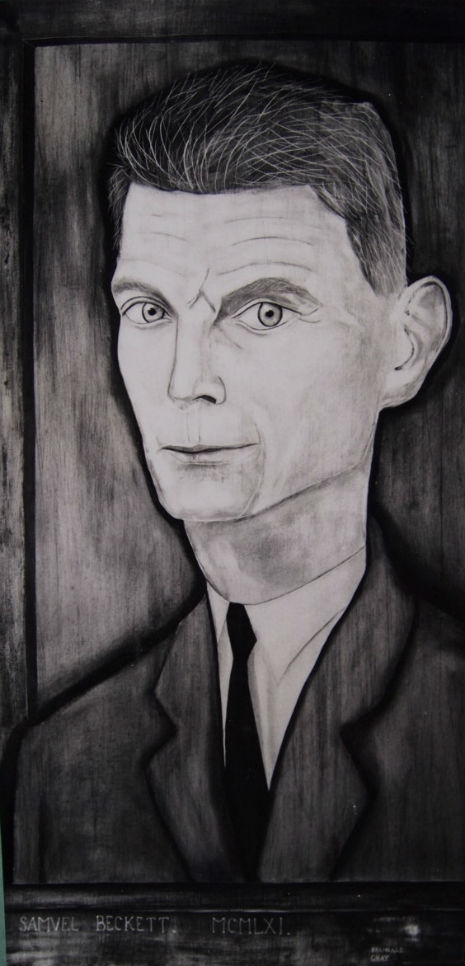

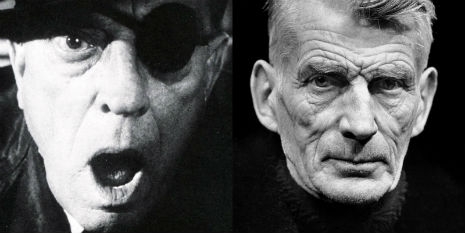

Writer Samuel Beckett’s only screenplay was for the 1965 avant-garde silent short, Film. Beckett, who made his biggest splash with the play, Waiting for Godot, always had an interest in motion pictures, having first tried to break into the business in the 1930s when he asked director Sergei Eisenstein if he could be Eisenstein’s assistant (the director never got back to him). For Beckett’s short, he recruited former silent film writer/director/star Buster Keaton for what turned out to be a very odd slice of cinema.

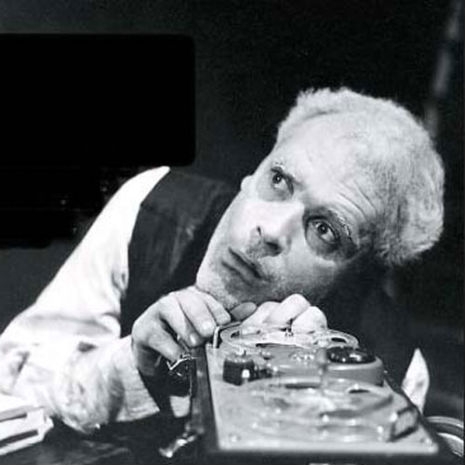

Film stars Keaton as a man on the run—but from whom? Seemingly paranoid, he sees eyes everywhere as he attempts to make himself invisible to everyone and everything. Film isn’t as gloomy as it sounds, as there are moments of both humor and slapstick that recall the films of the silent era. The short is open to interpretation, but according to Beckett, it’s about perception—self-perception, specifically—drawing on the philosophy, “To be is to be perceived.” With Film, Beckett was trying to tell us that we can run all we want, but we can’t hide from ourselves.

Barney Rosset of Grove Press, who produced the short via Evergreen Film, wrote about the making of Film in the pages of Tin House:

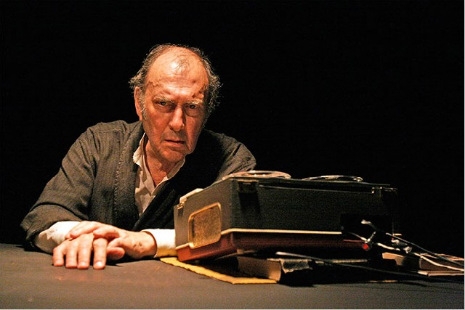

The first person Beckett wanted for the only major role in Film was the Irish actor Jack McGowran. He was unavailable, as was Charlie Chaplin and also Zero Mostel, Alan’s choice. Later, Mostel did a marvelous job with Burgess Meredith in a TV production of Waiting for Godot that Schneider directed. Finally, Alan suggested Buster Keaton. Sam liked the idea, so Alan flew out to Hollywood to try and sign Buster up. There he found Buster living in extremely modern circumstances. On arrival he had to wait in a separate room while Keaton finished up an imaginary poker game with, among others, the legendary (but long-dead) Hollywood mogul Irving Thalberg. Keaton took the job. During an interview, Beckett told Kevin Brownlow (a Keaton scholar) that “Buster Keaton was inaccessible. He had a poker mind as well as a poker face… He had great endurance, he was very tough, and, yes, reliable. And when you saw that face at the end… Ah. At last.”

Film has its share of fans, including director/film preservationist Ross Lipman. For the past seven years, he’s been simultaneously researching Film and putting together a documentary on the Beckett/Keaton work, resulting in Notfilm, a feature-length examination of a seventeen-minute short. Lipman also played a major role in the reconstruction of Film, as he located the original, long-lost prologue.

Here’s what Rosset wrote about the prologue in Tin House:

Originally, Film was meant to run nearly thirty minutes. Eight of those minutes would be one very long shot in which a number of actors would make their only appearance. The shot was based on Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, wherein Welles and his genius cameraman, Gregg Toland, achieved “deep focus.” Even when panning their camera, “deep focus” allowed objects from as close as a few feet to as far away as several hundred to be seen with equal clarity. Toland’s work was so important to Welles that he gave his cameraman equal billing to himself. Sad to say, our “deep focus” work in Film was unsuccessful. Despite the abundant expertise of our group, the extremely difficult shot was ruined by a stroboscopic effect that caused the images to jump around. Today it would probably be much easier to achieve the effects we wanted to capture. Technology is now on our side. Then, the problems proved too much for our group of very talented people so we went on without that shot. Beckett solved the problem of this incipient disaster by removing the scene from the script.

Now fully restored, Film will be included on the Blu-ray and DVD editions of Notfilm. There’s just one issue, lack of funds, so Lipman has teamed up with Milestone Films Fandor for a Kickstarter campaign. $30,000 is needed to complete the project and you can help make it happen. Check out their Kickstarter page to see all the incentives.

Here’s the trailer for Notfilm:

Watch Beckett’s ‘Film’ after the jump…