Everyone loves paperback movie tie-in novels. If you don’t, you really should. From their accessible prices and lurid covers to their not-always-screen-accurate content, this literary genre has provided joy for its fans for many decades. Reaching its peak in the 1970s as mass-market paperbacks along with genre novels of the romance, horror and sci-fi variety, the popular conception of media tie-in literature has been that it belongs to the more contemporary era of film and television work. Pop culture fandoms and collector advocacy have accelerated the idea that film novelizations are a recent phenomenon. Due to the observable vividness of their covers and the familiarity (or fucked-up bizarreness) of many of their titles, the movie tie-in paperbacks published from the 1950s onwards have become the standard by which we define the “movie novelization” or “movie tie-in” paperback.

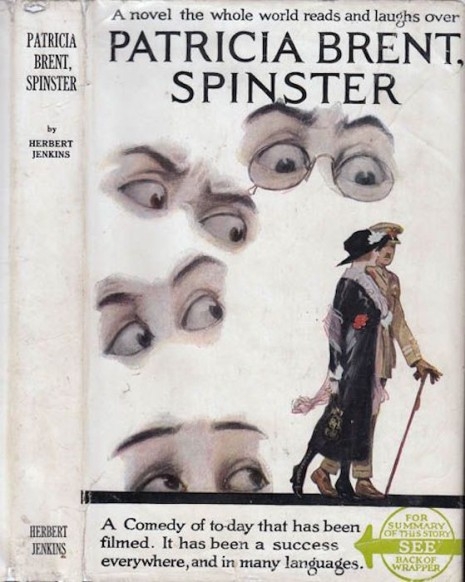

A few useful definitions: a novelization is a book based on a cinematic property. The writer uses an early version of the script or screenplay and, like movie tie-ins, these works are active parts of the film’s marketing. Tie-in novels are re-publications of previously written literary properties that films have adapted but with a “tie-in” feature to the upcoming movie. This could be a new title, a star on the book cover, etc. If a studio has changed the name of said book, the tie-in will carry the new name, not the original literary title (although the original name might be there as a “formerly known as”). A tie-in will also refer to books written after a film’s release in order to continue making money off the film property but have no connection to previously written literature. Both novelizations and tie-ins are pretty interesting. Obviously, some are more faithful to the, uh, original material than others.

Novelizations and tie-in paperbacks are still some of the most widely available of such items due to their large publication runs. You could buy them anywhere, put them in your back pocket, and they were cheap (in quality and in price). These titles, from the most cultish to the most famous, are the most talked about, well-known and collected movie-related books. Some of the older titles have even been reprinted. But these works were not the first in movie tie-in history. For that, you’ll have to start in the silent film era.

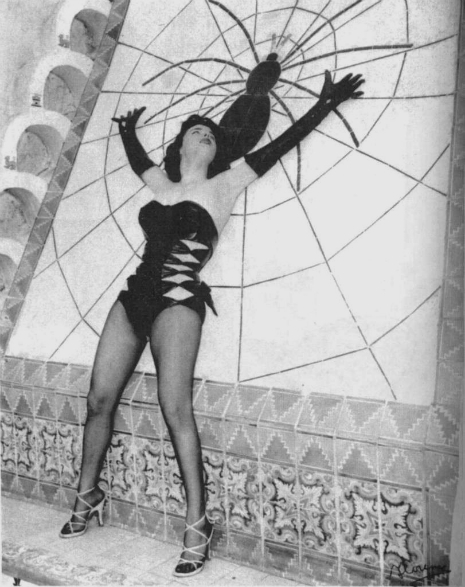

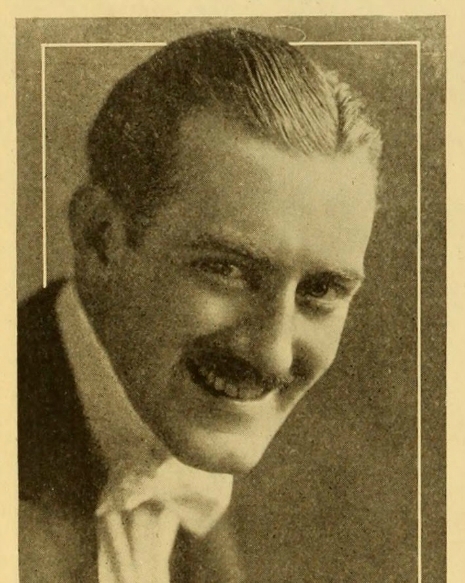

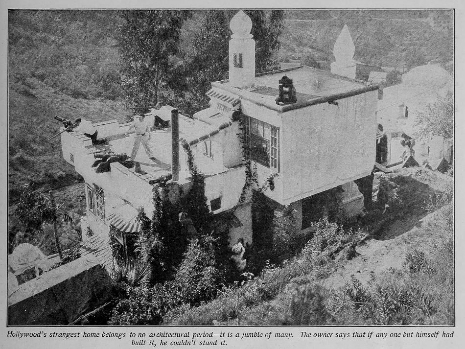

From the 1910s into the 1940s, Grosset & Dunlap and A.L. Burt were two of the main publishers of what are known as Photoplay Editions. This title came, of course, from the fact that they were designed to be released in tandem with the photoplays (aka films) that they were connected with. Yes, these were the first novelizations and movie tie-ins. These hardcover volumes had a similarity to their paperback brethren: they were rather plain on the inside. There was no gilding, no special binding, no ribbon bookmarks or dignified artwork, unlike many books of the time. On the other hand, they did include pictures from the film!!! Cool, right? These books were a brilliant marketing concept and the money the publishers saved on the fancy binding and silk endpapers? That got spent on the MIND BLOWING book jacket art.

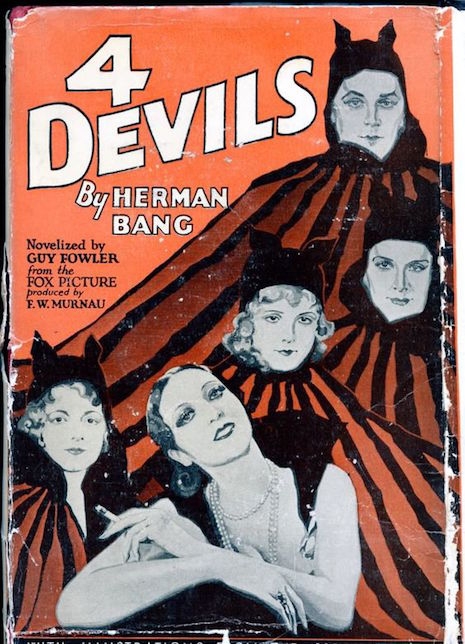

The most incredible part of these Photoplay Editions is that many still exist whereas the actual films they were promoting are considered lost. As a film archivist, I get the same tired jokes about finding Tod Browning’s London After Midnight (1927) all the time. Look, if it happens? You’ll be the first to know. But it won’t. The closest we may get is the beautiful Photoplay Edition that was released in conjunction with the film. And London isn’t the only lost film that we still have the book for. Murnau’s Four Devils (1928) also exists. And many more. Photoplay Editions are a virtual treasure trove- for movie tie-in fans, for film nerds, for art lovers. Enjoy these images!

More movie tie-ins and novelizations, after the jump…