Chester Himes’ early life was as disjointed and chaotic as the crime fictions he later wrote. Born into an African-American family in Jefferson, Missouri in 1909, Himes was witness to the racism endemic in the States at the time. His father worked as a teacher—he was the son of a slave and wanted to instil the value of education in Himes and his brother, Joseph Jr. Their mother thought she had married beneath her worth, and believed that being of lighter skin was the only way to progress in America—his mother’s emphasis on having a white skin color caused Himes some confusion (later reflected in his novels) of what it actually meant to be black. This mismatch of parentage led to an unsettling acrimony between his mother and father that pervaded throughout Himes’ childhood. His mother irreparably damaged the marriage by over-nighting in a “whites only” hotel. The following morning she told the management she was black. Word of the scandal caused Himes’ father to be fired from his teaching post and it was the start of his long and slow decline into poverty and failure.

The one event Chester Himes claimed filled him with guilt and anger was Joseph Jr.‘s blinding at school in a tragic accident. The brothers were to attend a chemistry class where they were to make gunpowder. After misbehaving, Himes was barred by his mother from attending the class. Joseph Jr. went alone, mixed the wrong chemicals—they exploded in his face. Joseph Jr. was refused treatment at the first available hospital because of segregation. By the time he reached a black hospital, it was too late to save his sight. As Himes later wrote in The Quality of Hurt:

“That one moment in my life hurt me as much as all the others put together. I loved my brother. I had never been separated from him and that moment was shocking, shattering, and terrifying…. We pulled into the emergency entrance of a white people’s hospital. White clad doctors and attendants appeared. I remember sitting in the back seat with Joe watching the pantomime being enacted in the car’s bright lights. A white man was refusing; my father was pleading. Dejectedly my father turned away; he was crying like a baby. My mother was fumbling in her handbag for a handkerchief; I hoped it was for a pistol.”

Himes left high school with below average marks, but had ambitions to continue with his education and passed entrance exams for Ohio State University. Himes was shocked to see the way in which his fellow African-Americans accepted the way they were treated by racist white students. His anger drove him to action. He was eventually expelled after a fist fight with a lecturer. Himes drifted and fell into a criminal life as a pimp, bootlegger and bank robber. He was arrested and sentenced to 20-25-years for armed robbery. Chester Himes was nineteen years old.

To pass his time in jail, Himes started writing short stories about prison life. These were sporadically published in various black magazines—eventually making it into the pages of Esquire magazine. Prison taught Himes how humans will do almost anything to stay alive.

“There is an indomitable quality within the human spirit that can not be destroyed; a face deep within the human personality that is impregnable to all assaults ... we would be drooling idiots, dangerous maniacs, raving beasts—if it were not for that quality and force within all humans that cries ‘I will live.’”

Released from jail after seven years, Himes started his career as a writer. His early books, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945) and Lonely Crusade (1947) examined elements of Himes’ ambiguous relationship to ethnicity and class.

“The face may be the face of Africa, but the heart has the beat of Wall Street.”

In later years, a friend wrote Himes saying he was “the most popular of the colored writers.” Himes responded:

“What motherfucking color are writers supposed to be?”

Himes was not easily swayed by simplistic political argument, and was critical of Left as much as he was of the Right. Instead he viewed his life as “absurd”:

“Given my disposition, my attitude towards authority, my sensitivity towards race, along with my appetites and physical reactions and sex stimulations, my normal life was absurd.”

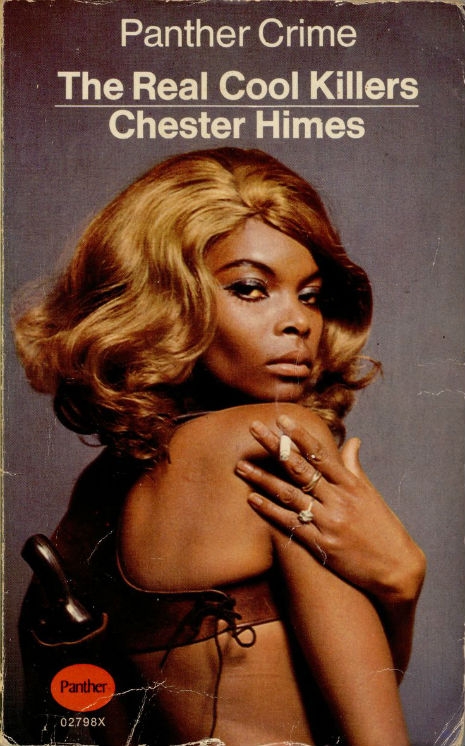

Himes never received the acclaim or the respect he deserved when a writer resident in America. It was only after his move to France that he was rightly acclaimed as a writer of great importance, power and originality. It was also in France that Himes began the series of crime novels (the classic “Coffin” Ed and “Grave Digger” Jones series, which included A Rage in Harlem and Cotton Comes to Harlem) that placed Chester Himes on par with Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett.

The following video clips give a good introduction to Chester Himes his life and work.

More on Chester Himes, after the jump….