‘Starving Artist’ by Ebony Lace.

A short while ago, Emily White, who is an intern at NPR, made a blog post in which she admitted that, despite having 11,000 songs on her iTunes, she had paid for a grand total of 15 CDs in her 21 years of existence. Is that statistic shocking? It certainly was to David Lowery, singer with Camper Van Beethoven and Cracker, who on Monday wrote a detailed, open-letter-style response to White.

This open-letter has been blowing up on social networks and music sites over the last few days, and I wanted to share it here as it’s pertinent to my own situation and I’m keen to see what other DM readers think. In the essay, Lowery asks White to think about how her actions and attitude has effected the music industry as a whole. He uses facts and figures to back up his assertions, and while not everyone is going to agree with what he writes, it’s an excellent essay that is well worth reading:

I must disagree with the underlying premise of what you have written. Fairly compensating musicians is not a problem that is up to governments and large corporations to solve. It is not up to them to make it “convenient” so you don’t behave unethically. (Besides–is it really that inconvenient to download a song from iTunes into your iPhone? Is it that hard to type in your password? I think millions would disagree.)

Rather, fairness for musicians is a problem that requires each of us to individually look at our own actions, values and choices and try to anticipate the consequences of our choices. I would suggest to you that, like so many other policies in our society, it is up to us individually to put pressure on our governments and private corporations to act ethically and fairly when it comes to artists rights. Not the other way around. We cannot wait for these entities to act in the myriad little transactions that make up an ethical life. I’d suggest to you that, as a 21-year old adult who wants to work in the music business, it is especially important for you to come to grips with these very personal ethical issues.

...

What the corporate backed Free Culture movement is asking us to do is analogous to changing our morality and principles to allow the equivalent of looting. Say there is a neighborhood in your local big city. Let’s call it The ‘Net. In this neighborhood there are record stores. Because of some antiquated laws, The ‘Net was never assigned a police force. So in this neighborhood people simply loot all the products from the shelves of the record store. People know it’s wrong, but they do it because they know they will rarely be punished for doing so. What the commercial Free Culture movement (see the “hybrid economy”) is saying is that instead of putting a police force in this neighborhood we should simply change our values and morality to accept this behavior. We should change our morality and ethics to accept looting because it is simply possible to get away with it. And nothing says freedom like getting away with it, right?

This article presents (in a roundabout way) two things I have been brewing over for a long time, in regards to file sharing.

The first one is this: why does the onus always seem to be on the creator of art to accept that their product should be free, rather than on the consumer to analyze the impact of their actions on the quality of art?

It has happened here on DM in the past, especially in heated comments threads under posts about Pirate Bay, where the question that tended to get asked the most was “why should an artist expect to get paid money for what they do?” (Unfortunately, since we switched over to the Disqus comment system last month, all our old comment threads have been wiped, but readers are more than welcome to keep the discourse going right here.)

Well, as an artist, the most immediate way to refute that question would be to ask “why should you expect to receive art for free?” But to take it further, here is another question that is never, ever asked, and to me taps into the root of the whole problem: “if you are not willing to pay for music, then why exactly do you collect music?”

Seriously, though. Why? Yes, music is lovely (I should know as I have dedicated my life to making, playing and writing about it) but then so is beer, and if I expected to get drunk every day without paying any money for the privilege, I would quickly get the reputation of being an unpopular scrounger. It’s basic economics, but it’s still a concept many fail to grasp, or would rather substitute with the victim-blaming that it’s the artist’s fault for expecting to get paid.

So, to put it more Marxist-friendly terms: “why does a person consume a form of art?”

I should make this clear at this point, I have been a very heavy collector and consumer of music myself in the past, my forte being rare disco and obscure deep house. So I get it! I get the buzz of obtaining new music (not to mention that, being a DJ, I need to have access to new music). But there came a point when I realized that NO, I couldn’t own every single disco record ever made—thank you, Daniel Wang—but also, why in the hell would I want to?!

As a musician I have found that I learn more about music by concentrating on a smaller group of records/artists and listening to them more intently than I do from consuming vast swathes of music and not really getting around to listening to much of it. While a lot of this has to do with my own route from consumer to creator, the thought still niggles at the back of my head: have music consumers been driven into such a blind state of consumption that they simply MUST have everything, regardless of the cost to the medium itself?

And I ask this because sometimes it feels like the artists, the people who make our society more tolerable, more beautiful and even more inspirational, have been thrown to the wolves. One of the most common “validations” for the file sharing of music among consumers and listeners is that the labels have been exploiting us for years, so fuck ‘em. While this may be true, it’s very short-sighted and supremely selfish, as it (deliberately?) disregards the damage caused to the artists and, in turn, the musical landscape by the devaluation of the actual product. And while their work has been deemed financially worthless by the people who consume it (people who, presumably, want to hear/read/see/feel more of what the artist has to offer), what opinion do artists most often hear coming from the public in relation to art? That the quality is getting worse and worse. Well, I’m afraid these two things are not unconnected.

And here’s the second point that really irks me.

First and foremost, beyond being a writer and a blogger, I consider myself a musician. I create music regularly, I work hard at it, and I try and funnel all my non-music-creating activities back into helping me make more music. One day I would dearly love to be able to live off the money generated by my music. So, am I somehow wrong (or perhaps even evil) because I want this?

Some would say that I am, that somehow I am not a “true” artist because I have brought money into the equation and have aspirations to become “professional.” (How exactly does being considered a professional in your field invalidate what you do?!) To these folks I must stay clean and unsullied by money at all times, lest I become some kind of artistic “whore.” (And I LOVE getting called a “whore,” especially by people who can’t stop themselves downloading music like a junkie can’t say no to a fix.)

Well, newsflash: your romantic notion doesn’t pay my rent.

I need money to go on creating my art. I need money to live, and to peruse that at which I am good at. I need money to invest in the equipment I need to make music. I need money so I can spend time learning how to use that equipment properly, not to mention spending time on that actual art of music itself i.e. writing and arranging melodies, rhythms and lyrics. I need money to finance distribution in all its forms and the production of physical media. If I am to progress and be the best artist I can possibly be, I need the time and money afforded by being a professional in my field. I could make some bucks out of t-shirts sales, I am told, but I am not in this to be a t-shirt designer. I am in this to be a musician.

And another point that I should clarify: I have been heavily involved in “free culture.” From 2007 till this year I ran a label that dealt primarily with free downloads. I have released music through other labels that work on a similar basis. Simply put, I love giving people some of my music for free. But not all of it. If I have a potential Number One song in my brain, something I feel could give me an ongoing, long-term income, and thus the freedom to peruse my art to a higher level, why would should I give that away for free?

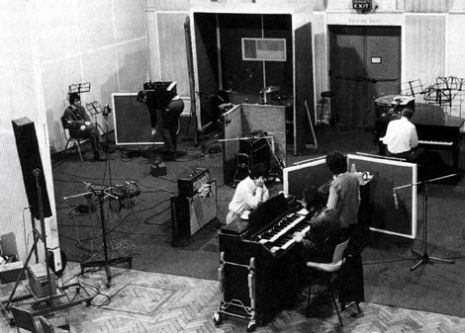

I will always go on making music, of course. I don’t think I will ever stop playing with my Ableton and my Akai controller (until something better comes along) and I know now that, even if I wanted to, I couldn’t stop my brain writing strange little melodies all on its own. But while I will go on making music, I will also keep feeling the frustration of not being able to reach my full potential, of not progressing and of missing opportunities of creating bigger, wilder, greater art. Of using 40-piece choirs and 24 track analog desks, of playing around with original Moogs and top of the range compressors. And where exactly would the incentive for me to share my music with the world be, if the world isn’t willing to share something in return?

As uncommercial or abrasive as my music sometimes is, I consider it to be worthy of as big a fucking audience as possible. I don’t want it to stay in a niche, preaching to the already converted, I want it to travel and affect as many people as it can. And that’s another thing that costs money. Simply “putting it out there” is NOT enough, artists are still reliant on proven methods of PR and old/new media communications to make people aware of their work.

Here’s a case in point. Last year I made an album, and after punting it around to various labels who turned it down, I decided just to put it out there for free. It’s called “AKA” and there are a lot of guests featured, many of them MCs and vocalists from underground gay and drag scenes, but they all have something unique, refreshing and different to say. I want to give them the biggest platform I possibly can to get their messages across. So go at it, get the album, (directly here, or listen first here) it won’t cost you a thing, and if you don’t like it, you can have your money back. But I will still have to invest money in this project to see that it goes beyond small niche markets and has a chance of being picked up in the mainstream. Because I believe it deserves to be in the mainstream.

“AKA” is my fourth free download album release, and I hope it is my last. Not because I dislike giving away my music for free, or because I want to start sucking corporate cock. But because free culture is not sustainable, not for me anyway. Or for artists who want to progress beyond the bedroom and take their work out to a mass audience. An audience that is constantly telling us it WANTS and NEEDS new and exciting music, maybe the very kind of music we are creating. For artists who want to kick it up a level and become *gasp* professional musicians. Not t-shirt designers, not concert promoters, not writers-who-make-music-on-the-side, but PROFESSIONAL MUSICIANS.

Asking for money for your output is NOT a crime. No-one is expecting to get rich off music, just to be paid our dues.

I may be wrong, but I believe that we’ll never see another David Bowie or another Prince or another Beatles again. Not because talents such as there’s aren’t out there, but because the financial system that allowed those talents to flourish, and that in turn made the consumers used to obtaining a high level of art on a regular basis, are gone. That is in no way an excuse for the almost-criminal activities of major labels, and smaller labels for that matter, rather it’s just a statement of fact. Without access to the high calibre musicians/producers/engineers/designers/promoters/managers/etc that was afforded these artists through the label network, none of them would have been able to create their most seminal works of art, works that defined eras, inspired movements, elevated art forms. And, lest we not forget, raised the expectations of listeners to such a level that all else pales.

The public WANTS another Beatles/Bowie/Prince, an iconic, genuinely brilliant artist or band, for and of our age, yet to me the public doesn’t seem willing to pay for that.

So where do we go from here?