If you’re at all aware of comic books history, Jack Kirby needs no introduction. As one of the founding visionaries at Marvel in the 1960s, Kirby’s vital storytelling skills and phenomenal visual energy helped make the X-Men, the Hulk, and the Fantastic Four household names.

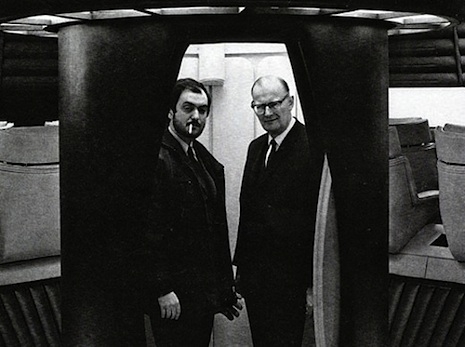

A few months ago we drew your attention to a never-published project of Kirby’s, his adaptation of The Prisoner, the dystopic British TV series starring and co-created by Patrick McGoohan. Today we have a similar treat, one of the very few fully realized stories by Kirby that has never been collected in book form—his mid-1970s adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey, originally a short story by Arthur C. Clarke called “The Sentinel” and later a movie directed by Stanley Kubrick.

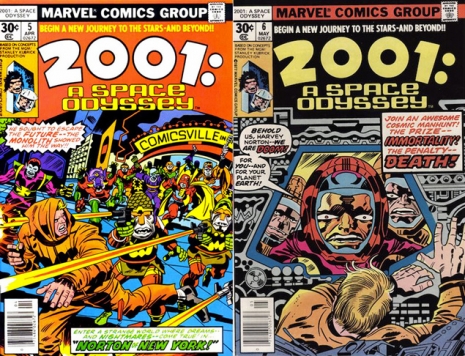

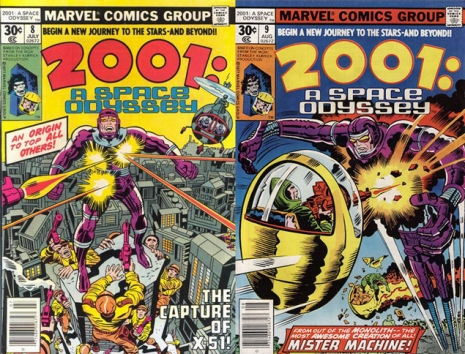

The movie came out in 1968, but Kirby’s adaptation had to wait until 1976. We can regard that gap as a kind of marker for Kirby’s strong desire to adapt the story even though there may have been little commercial interest in it. Kirby first adapted the movie as a standalone book of 70 pages, and then proceeded to recapitulate the movie’s plot and themes over and over again across 10 issues—except this time with scary aliens with tentacles that have nothing to do with Kubrick’s movie. The resolution of that 10-issue run is a character who is actually oddly resonant with our own times, a human-A.I. hybrid called Machine Man, whose own comic book line, which picked up where 2001: A Space Odyssey left off, lasted for a few months. The character would be fitfully resurrected every ten years or so (1984, 1999).

Remarkably, Machine Man was eventually made a part of the Avengers, so it’s an accurate statement to say that the Avengers has the DNA of Kubrick and Clarke in it—and for that matter Friedrich Nietzsche, who is never far from my thoughts whenever I watch Kubrick’s masterpiece.

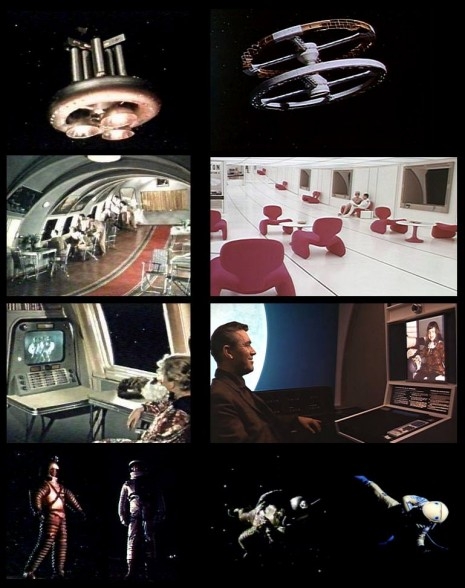

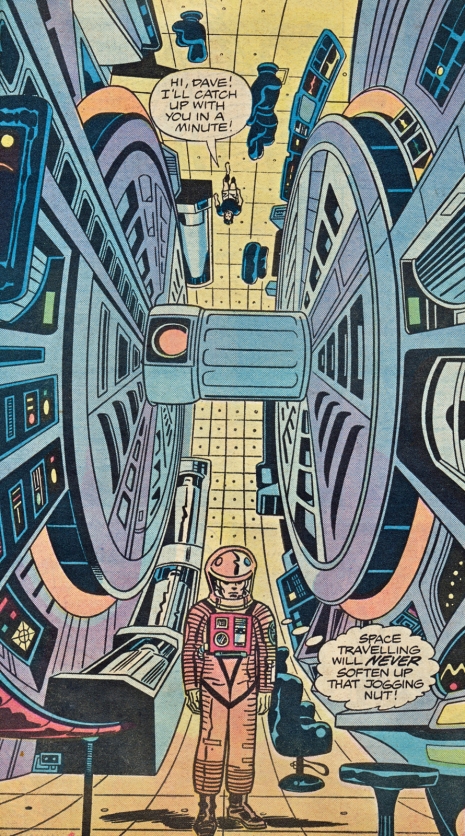

Kirby’s adaptation of the movie was wildly rethought for the medium of comics. His palette is all over the place, departing vastly from Kubrick’s more stately blacks, whites, and reds. And the action of course is tuned to the entertainment value of a typical 10-year-old rather than a stoned college student—this is echoed in the cover promise that “The Ultimate Trip” would become “The Ultimate Illustrated Adventure!” Kirby dispenses with the three (highly Nietzschean) sections of the movie (“The Dawn of Man,” “Mission to Jupiter,” and “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite”) with four more hyperbolic sections of his own, which are replete with exclamation points:

Part I: The Saga of Moonwatcher the Man-Ape!

Part II: Year 2001: The Thing on the Moon!

Part III: Ahead Lie the Planets

Part IV: The Dimension Trip!

Kirby’s fans are said not to be fond of his 2001: A Space Odyssey, but I must say I like it. It’s got not that much to do with Kubrick but that just makes it all the more interesting.

In Kirby’s telling, the so-called “Starchild” infant of the movie’s finale is reconcieved as “The New Seed.” In the feature hilariously called “Monolith Mail” reserved for reader correspondence, Kirby noted of this element:

The New Seed is the conquering hero in this latest Marvel drama. Why? Because he has staying power, that’s why. He will always be there in the story’s final moments to taunt us with the question we shall never answer. The little shaver is, perhaps, the embodiment of our own hopes in a world which daily makes us more than a bit uneasy about the future ... in the meager space devoted to his appearance, he brightens our hopes considerably. He is a comforting visual, almost tangible reminder that the future is not yet up for grabs. And wherever his journey takes him matters not one whit to this writer. The mere fact that the chances of his making it are still good is the comforting thought.

Some sample images from Kirby’s 2001: A Space Odyssey:

More images from Kirby’s 2001: A Space Odyssey after the jump: