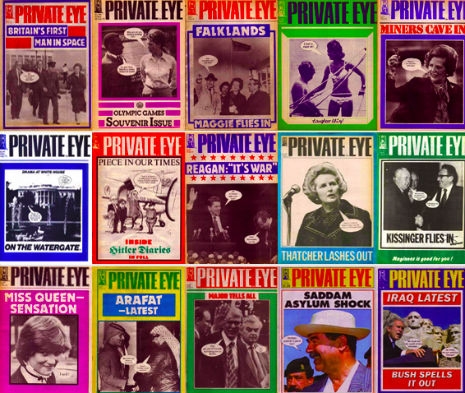

1976 was a difficult year for the satirical and current affairs magazine Private Eye.

This was the year its then editor, Richard Ingrams received over 60 writs from disgruntled billionaire businessman Sir James Goldsmith (aka Sir Jams Fishpaste, as the Eye called him). Goldsmith had objected to 3 stories the Eye had published about him—one in particular that suggested Fishpaste had helped his friend, Lord Lucan escape Britain from a murder charge.

Goldsmith and Lucan were bonded by several things, one in particular was a belief Communists had infiltrated western media, and Britain was on the verge of a Communist revolution. It led Fishpaste and Lucan to discuss the pros and cons of a Fascist military coup over “smoked salmon and lamb cutlets.” Their conversation reflected the paranoid, Boy’s Own fantasies of a very privileged and ruthless class.

But “Goldsmith was angry, as well as rich,” as one of Private Eye‘s lawyers, Geoffrey Bindman later explained:

“[Goldsmith] set out to destroy the little magazine that had presumed to offend him. He sued….But he spread the net far beyond Private Eye. In a novel exercise in overkill, he issued separate writs against all the distributors and wholesalers of the magazine. There were over 60 writs. Private Eye faced a huge financial burden. It was liable to indemnify all those whom Goldsmith had chosen to sue.

The first task was to reassure the recipients of these writs that the indemnity would be honoured. Private Eye lacked the resources but had a lot of supporters. A drive to raise money began, inspirationally named the Goldenballs Fund.

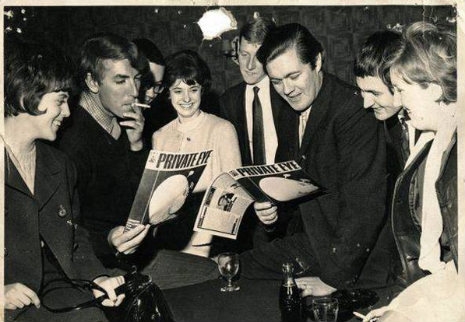

Peter Cook and Richard Ingrams check an early edition of ‘Private Eye’

The legal action brought considerable media attention, and in October, the BBC made a documentary about Ingrams and Private Eye:

“Richard Ingrams’ offices are at 34 Greek Street. A former haunt of prostitutes and drug addicts. Now the main problem is writ service. Rented at sixty-pounds-a-week, the building is small and dilapidated, but it’s all that Private Eye can afford. The magazine runs on a shoe-string budget. It comes out once a fortnight, price 20 pence, and has a circulation of 90,000.”

Ingrams may have looked like an unassuming university lecturer—dressed in a corduroy jacket, with a Viyella shirt and tie, but he was (surprisingly) a reformed drinker and smoker, who believed in God and played the organ at the local church. He was, more importantly, a superb and strongly principled editor, who understood Private Eye‘s role:

“It has to be anarchic. It has to be prepared to hit everyone—even its friends. As long as you attack everybody indiscriminately, completely indiscriminately you are safe. Immediately you start taking sides, or sticking-up for somebody, or keeping quiet, then you get into difficulties.”

Under his editorship, Private Eye had a golden decade in the seventies. It attracted some of the very best writers, journalists and artists, who brought an excellence other magazines (Punch) could only dream about. There was Auberon Waugh who produced an hilarious and corruscating diary; Paul Foot who delivered brilliant investigative reports; Peter Cook offered memorable comic contributions; and “Grovel” the Eye‘s (in)famous gossip column written by the late, Daily Mail diarist, Nigel Dempster, who claimed:

“We live in a banana peel society, where it gives no-one greater pleasure than to see someone trip up.”

Not all of the Eye writers were happy with Dempster’s column, Christopher Booker thought it edged too close to exaggeration, without thought of the damage done.

This lack of thought had led a 100 people to sue Private Eye by ‘76, which had depleted much of the magazine’s profits. But then the Eye was never really that interested in profits—it was a product of those patrician attitudes Public Schools can afford to inspire.

The magazine’s original quartet Richard Ingrams, Christopher Booker, Paul Foot and William Rushton had all met at Shrewsbury School, where they had produced their own teenage satirical magazine—a first issue was covered with hessian and embedded with free seeds. After school, university, where Ingrams hoped to become a leading comic actor. It didn’t happen, and the Famous 4 regrouped to produce the very first Private Eye in 1961, from typescript, Letra-set and cow-gum. It is interesting to note how this amateur, home-made style has remained very much the template for the Eye ever since.

This new magazine chimed with the so-called satire boom, in which Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller conquered the world with Beyond the Fringe, and producer Ned Sherrin made a star of David Frost (who Booker later described as a man with “..a peculiar ambition to be world-famous simply for the sake of being world-famous”) on the highly successful That Was The Week That Was—which proved so successful it was canceled after 2 series.

The Eye continued long after both these shows and the satire boom had run out of laughs, in part much aided by the backing of Peter Cook, who helped finance the magazine until his death in 1995.

What makes Private Eye essential is the ephemeral nature of its exceedingly good journalism. As Auberon Waugh once wrote (in the introduction to Another Voice—his essential collection of writing for The Spectator), “Timeless journalism is bad journalism”:

“The essence of journalism is that it should stimulate its readers for a moment, possibly open their minds to some alternative perception of events, and then be thrown away, with all its clever conundrums, its prophecies and comminations, in the great wastepaper basket of history.”

Though it has been occasionally wrong (MMR comes to mind) and wrong-headed (comic attitudes towards race, women, and gays have been questionable), Private Eye is indispensable and essential reading for those with an interest in the follies of politics and business of contemporary life, or the strong tradition of good investigation journalism, which most newspapers appear to have abandoned long ago. This is what made, and still makes Private Eye truly great.

Sir Jams Fishpaste launched his own magazine Talbot!, which soon disappeared without trace, before forming the I Can’t Believe It’s Not Margarine Party, a popular movement that failed to be..er..popular. He died in 1997.

Richard Ingrams quit Private Eye in 1986, and appointed alleged schoolboy Ian Hislop as Editor, who has managed the magazine with great success ever since.

Ingrams started a new magazine The Oldie in 1992, which has been described as “the new Punch and the new New Yorker,” which he continues to successfully edit today. Richard Ingrams is 94.

Check Private Eye online here.

With thanks to NellyM