That great American blues/folk artist Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter was born on January 20, 1888 (or 1889), making today the 127th (or 126th) anniversary of his birth. He’s known today for popularizing songs like “Goodnight Irene,” “Midnight Special,” and “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” as American folk and, eventually, rock ‘n’ roll standards, but in his day, Lead Belly was widely renowned for having been in jail. A lot. Thrice, in fact—once on a weapons charge, once for killing a man, and a third time for trying to kill a man.

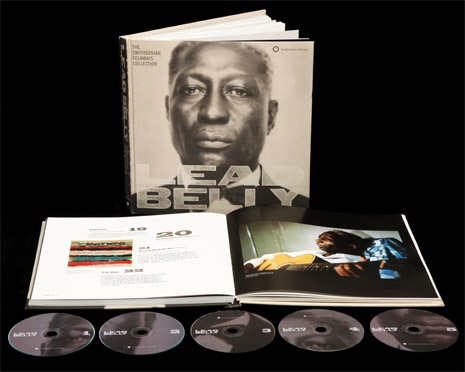

Remarkably, Lead Belly literally sang his way out of prison! His second stint was cut short by a pardon issued after Lead Belly wrote a song honoring the then-Governor of Texas Pat Morris Neff, and he repeated the stunt during his third hitch, in Louisiana (though as he may have been eligible for a good-behavior release anyway, it’s disputed whether it was really the song that did the job). It was while he was serving that third sentence that Lead Belly was recorded in performance by the famous father-son team of folklorists John and Alan Lomax, which of course is how we know him today. From an essay by Smithsonian Folkways archivist Jeff Place, which will appear in the forthcoming 5-disc retrospective Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, and which we’ve edited for length:

Angola was one of the worst prisons in the South; it was probably as close to slavery as any person could come in 1930. Lead Belly became known around the prison for his singing and guitar playing. This was the situation when John Lomax wrote the prison warden L.A. Jones about visiting on behalf of the Library of Congress to record prison songs.

John Lomax and his young son Alan were traveling and recording African American folk songs in prisons in the South. They were hoping to find older African American vernacular music not “contaminated” by the popular blues and jazz of the present day, and they felt long-term prisoners who had been isolated from society might just be the answer. Fresh from recording some of Lead Belly’s fellow prisoners at Sugarland on July 5, 1933, they arrived at Angola on July 16. Lead Belly was suggested to them as a good singer to record, and they realized they had really made a “find.”

The Lomaxes made 12 recordings. Lead Belly saw an opportunity in this situation for himself and “wondered if a pardon song” might work again. Unlike Neff, Louisiana governor O.K. Allen did not tour prisons, so Lead Belly didn’t have access to him. When the Lomaxes returned the following July to record 15 more songs, he had a special one prepared, “Governor O.K. Allen.” He asked if John Lomax would deliver a recording of the song to Allen’s office. Lead Belly had previously written asking for a pardon as well. It is not known whether Allen listened to the song, but Lead Belly was officially granted a pardon on July 25, 1934. Again, the state maintained it was purely on the basis of “good time.”

Lead Belly’s meeting with the Lomaxes was re-enacted for a short newsreel film that, luckily, survives. Here it is, featuring Lead Belly and John Lomax woodenly playing themselves, with a darkened garage standing in for a prison yard. It’s kind of ridiculous, and to a viewer today it’s full of embarrassing values dissonance (loads of “yassuh” racism, unsurprisingly) but on the other hand, it’s motion footage of Lead Belly performing “Goodnight Irene!”

After his third release, in 1934, Lead Belly made a go of a singing career, abetted by the Lomaxes, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, and tantalizingly lurid newspaper descriptions like “Murderous Minstrel,” “Virtuoso of Knife and Guitar,” “Two-Time Dixie Murderer Sings Way to Freedom,” and by far my favorite for its sheer over-the-top sensationalism, “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here to do a Few Tunes Between Homicides.” Lead Belly fell out with Lomax in 1935, but his career continued, and in 1948, he would make his final recordings. Again from Jeff Place:

During the 1940s, Lead Belly met two individuals who would become important to his final years of life, Frederic Ramsey Jr. (1915–95) and Charles Edward Smith (1904– 70). Both men were record collectors and jazz scholars and had recently jointly published a book, Jazzmen (1939). They were interested in researching early African American music from the South to search for the roots of jazz. Lead Belly’s repertoire was a perfect resource in this quest. Ramsey felt that Lead Belly’s repertoire had been under-recorded and wanted to get as much of it as he could on tape.

Ramsey got to know Lead Belly socially after the war. “Lead Belly used to come up and visit, and people would come and visit, and we would really throw parties, and you couldn’t stop that guy from performing. I mean, he did it, you could have paid him nothing, he’d come there and have a good time and he would play”. One night Huddie and Martha were invited to the Ramseys for dinner, and Ramsey showed Lead Belly the new machine. Ramsey had hung drapes in his apartment to simulate the sound dampening in a recording studio. Lead Belly wanted to try it out, although he had not brought his guitar, not planning on playing. Ramsey had only a cheap microphone. With Martha’s occasional help he recorded 34 songs that night. Better yet, the tape deck allowed the recording of the introductions and the stories behind the songs. There would be three evening sessions (with the guitar at the other two, along with much better RCA mics borrowed from Moe Asch), and more planned. Lead Belly left for a European tour before additional sessions could be arranged. “Anyway, I think we had maybe three or four gatherings, and I could be wrong about this, it certainly wasn’t all done in one evening, but he used to come and once he… he was a guy who got really comfortable, once he got started, he wouldn’t stop.”

That many of these last recordings were recorded unaccompanied was sadly prophetic. Lead Belly would soon be exhibiting the symptoms of ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease), which robbed him of his ability to play before took his life near the end of 1949.

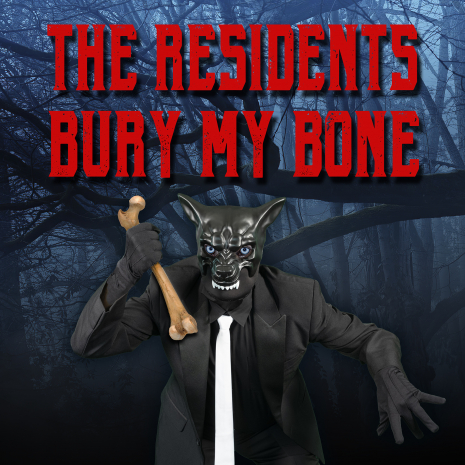

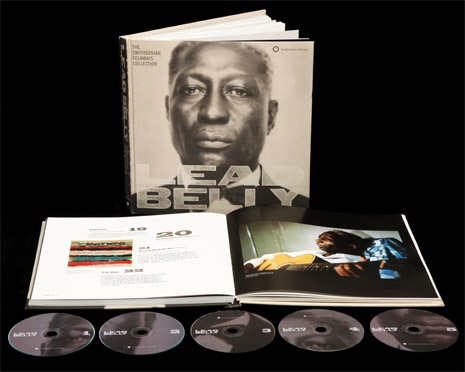

The aforementioned Folkways set, Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, is the most comprehensive career-spanning retrospective of his work yet, and is scheduled for release on February 24th, 2015. Packaged in a 140 page 12x12” book, it features over 100 songs on five discs, 16 of which have never been released. One of those unreleased songs comes from that guitar-less session at Frederic Ramsey’s apartment. It’s called “Everytime I Go Out,” an original composition that doesn’t appear to have ever been recorded in any other form. We at Dangerous Minds are thrilled to be able to debut it for you today.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

The only film footage of blues/folk legend Leadbelly

Kurt Cobain and Mark Lanegan’s short-lived Leadbelly tribute band

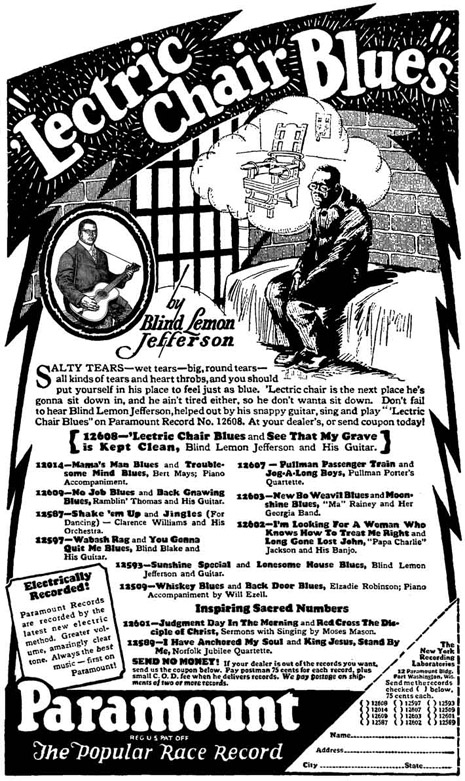

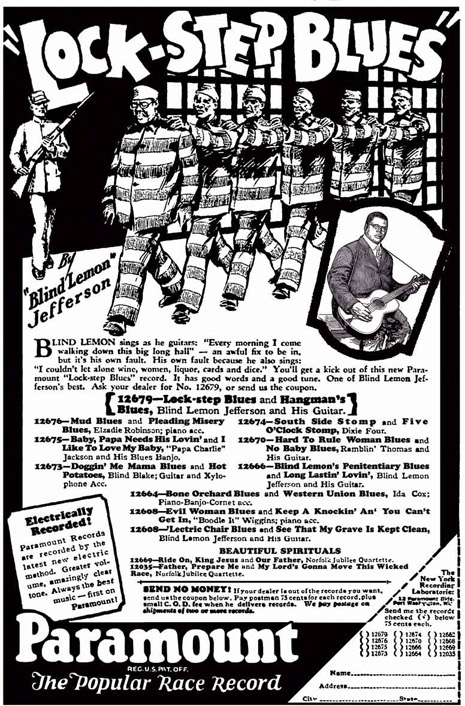

The amazing old Paramount Records ads that inspired R. Crumb