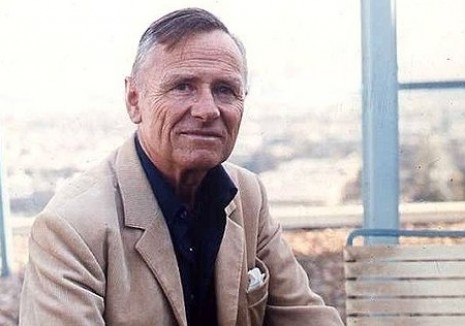

DV8 Physical Theater was formed in 1986 by dancer and choreographer, Lloyd Newson. Over the past twenty-five years, DV8 has produced 16 internationally successful dance pieces and 4 award-winning films for television.

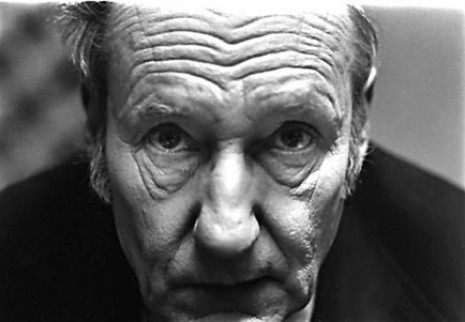

From the start Newson’s work has been controversial. In 1990, the Sunday Mirror denounced DV8’s television production, Dead Dreams of Monochrome Men, a piece inspired by the career of the serial killer Dennis Nilsen, as a “Gay Sex Orgy on TV”. Such “rabid headlines” gave the program an unexpected boost. It also revealed Newson’s considerable intelligence at work behind DV8’s provocative performances. As he explained in an interview with Article 19

One of the things about DV8’s work is it is about subject matter, for a lot of people who go and see dance it is not about anything and DV8 is about something. I think the other thing that is important is the notion of humour and pathos, of tragedy, of multiple emotions and responses to my work –I’ve been so tired over the years of watching so much dance on one level, it may be very pretty, but it just goes on and on, it’s pretty nice, pretty much the same and pretty dull really, a lot of it.

So my big concern is to try and present images through movement and to talk about the whole range of social and psychological situations.

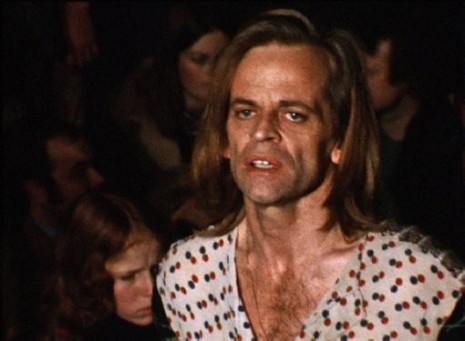

In 2004, DV8 made The Cost of Living, for Channel 4 television. Based on a longer performance piece, The Cost of LIving was devised by Newson and the dancers, who range from “extremely able-bodied to a man with no legs,” David Toole whose incredible performance challenges our perceptions about ability and adds to the film’s “critique of society’s obsession with image.” As Newson explained in 2004:

The Cost of Living is very much about those people who don’t fulfill the market value, in the sense of playing on the words the cost of living in terms of the financial issue and looking at what happens through experience as you live do you lose your naiveté? As you live do you lose a lot? Or does experience assist you?

What I’m interested in [with] this piece is: do you become cynical and bitter as the cost of living, or do you not? So we’ve got lots of different characters; those who play the more embittered ones, we have the notion of Stepford [Wives] the idea that it’s important for all of us to join the club, whether it be dressing well, being attractive, being successful, and if we can’t be really successful financially or in terms of fame or celebrity, at least we can be normal.

But what happens to those people who don’t fit into any of those categories?

So there are lots of different parallels – dance is a beautiful parallel. So much of dance is about the youthful, beautiful, slender, able-bodied performers. Dance I think is a great form to talk about these issues. It’s a bit like a beauty contest, in fact we have a beauty contest or a physical contest, so underneath all the smiles and attractive bodies on front covers of magazines we want to know what else is going on; who has had the tucks, who is hiding their faults.

Some people can’t hide them as much as others, we have a disabled performer in the company, we have a very large, fat dancer, and on a very obvious visual level they look very different to us.

So what about those people on a psychological level who may be able to hide their physical imperfections, but [cannot hide] their psychological imperfections and why is it so important that we have this ‘Prozac face’? I used to refer to dance as being the Prozac of the art forms. So that is what the piece is about – it’s about those who aren’t perfect and who can’t pretend, those who don’t fit in because they don’t play the game.

There is also the notion throughout the piece about rules. We have a big LED board that has displays about certain rules. The whole set is made of what appears to be fake grass and the board reads like a sign in a park, or a traffic sign “keep off the grass”, also at times it tells the audience and the performers what to do. Do they obey those rules? They’re some of the ideas we’re playing with really, who sets the rules who follows the rules.

So it’s pretty epic in what it’s dealing with.

The rest of ‘The Cost of Living’ after the jump…