Of the so-called Krautrock bands, Harmonia’s music is the most beautiful. It often sounds as if they’re playing colored lights rather than musical instruments. As Julian Cope writes of Harmonia’s first album in Krautrocksampler:

Each piece was a short vignette of sound which faded in, filled the room with its unearthly beauty, then left just as quickly.

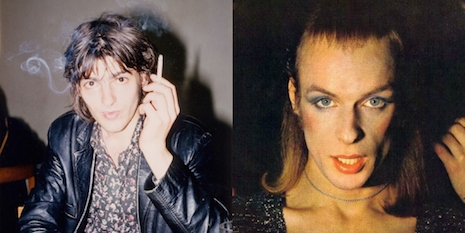

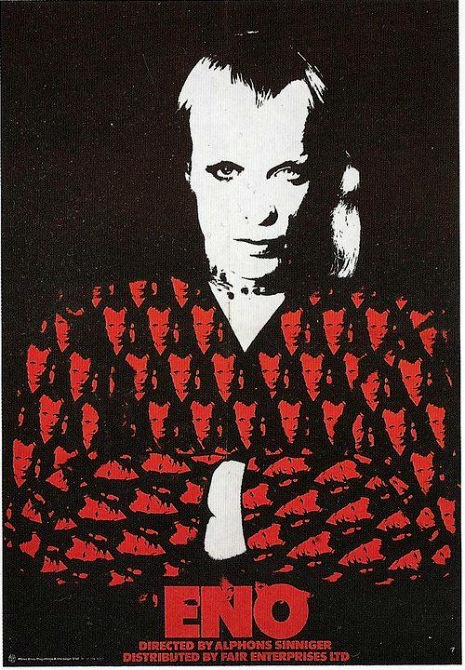

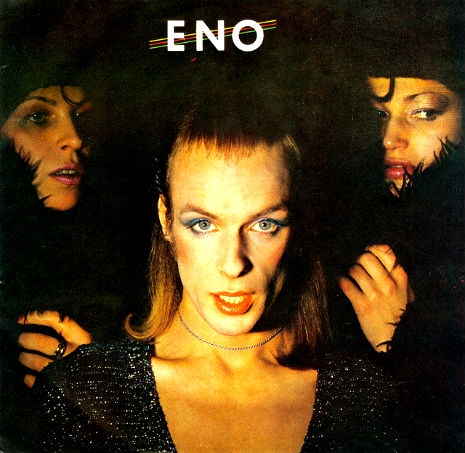

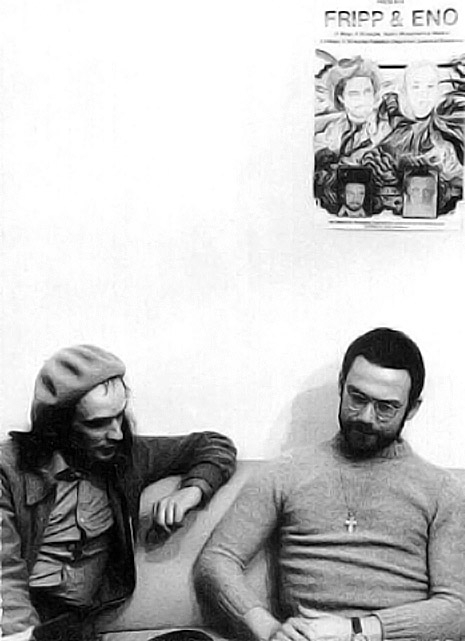

Formed in 1973 by guitarist Michael Rother, who had founded NEU! after leaving Kraftwerk, and electronic musicians Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius, who played together as the duo Cluster, Harmonia lived and recorded in a communal setting in the rural town of Forst, where Rother still lives. Brian Eno, who believed Harmonia was “the world’s most important rock band,” traveled to Forst to record with the trio in 1976, after the group had already agreed to break up; he described what he found there as “a small anarchic state.”

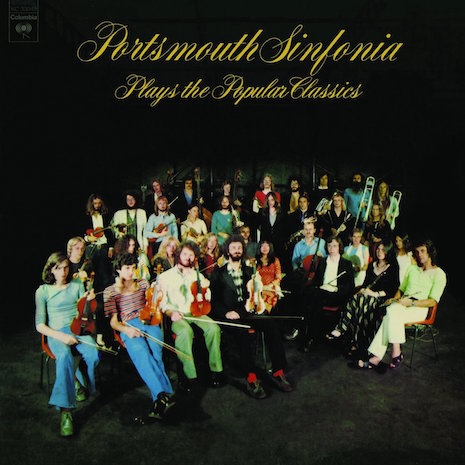

Harmonia only released two albums during their brief career, both essential: Musik von Harmonia and Deluxe. Tracks and Traces, the album resulting from Harmonia’s collaboration with Eno, did not come out until 1997; a decade later, the release of Live 1974 brought the total number of Harmonia records to a slim but sturdy four. On October 23, Grönland Records will release Harmonia’s Complete Works, a five-LP box set that supplements all of the above with a new archival release, Documents 1975, a poster, a pop-up, and a booklet with photos from Forst and an enlightening essay by Geeta Dayal.

I spoke with Michael Rother about Harmonia’s remarkable career early one morning in September.

It strikes me that you have a really distinctive guitar tone. I feel like if someone was playing a recording of yours that I’d never heard before, I could identify that it was you. Do you have any insight into how your tone developed?

Of course, this is a compliment. Actually, it should make me happy. It makes me happy—and maybe it’s also true, to a certain degree—but there is no real secret about the guitar. I think it has to do with the way I play guitar.

I used to, in the sixties, when I was still a copyist, a copy guitar player, copying heroes like Harrison, Clapton, Hendrix, Page, and whatever [laughs], I tried to play the rock’n’roll, rock type of guitar. But I stopped that in the late sixties, and the idea was to throw away the fast fingers and concentrate on one note, and then gradually find out what I can express on the guitar without being a copy of someone else.

And, of course, maybe you’re right, the fuzztone is special. I have a fuzz—the original was built for me in the seventies, but not NEU! so, see, it can’t be the only explanation—that was built when I was with Harmonia, by some people in the vicinity, music fans and also musicians. And this guy built a copy of, I think it was a copy of a Big Muff or something like that for me. In recent years, I was lucky that a real audio guru, a real, very talented, experienced studio electrician—electrician, maybe not; like, he knows all about studio technology, and he can build stuff—so I asked him to rebuild that fuzz, and to build it in a slightly smaller case, so that I can carry it around the world. And he laughed when he looked at the original copy from the seventies, and said “Ha, ha! These people have made a mistake!” And I asked him to stick to that mistake, because maybe the mistake is partly responsible for the special sound.

But I think—that is probably one aspect, but the idea behind the guitar playing, how I build up several guitars in one track, I think that’s also a very important factor, creating some individual sound. When I started with NEU! I remember I had this vision of making my guitar sound like an oboe, you know, the wind instrument? Like, fading in? So I had these two volume pedals, and if you listen to tracks like “Neuschnee,” for instance, you hear an example. And by EQing the guitar, and then also, of course, adding delays, et cetera. But the idea of a guitar not sounding like a guitar was something that was, from the beginning, in my head. It was supposed to sound different.

I have to admit that I always pictured Harmonia’s music coming out of the city, in more of a laboratory setting, so I was really surprised to see in the booklet that comes with the box set that it was more of a communal situation with dogs and families… there’s one picture of a guy named Jerry Kilian lying on a couch with a beer bottle underneath. What can you tell me about life at Forst?

That’s an interesting thing, what you say about how you imagine the music to come from the city, because sometimes people say the opposite, and they ask me questions like, “Do you think the music by Harmonia could have been the same if you had, for instance, lived in Berlin, and recorded music in an underground studio without fresh air, without any windows?” Of course, it’s hypothetical; I have no real explanation. But what I try to say to those questions is: I believe that Roedelius, Moebius and I already had some kind of vision for the music which would have been independent of the place where the music is played. But, of course, partly the wonder for this magical place—because it’s not only the communal aspect, it’s also looking out of the window and seeing a river and fields, no human structure in sight, and to have this kind of open space—at least, it was something that appealed to me straight from the beginning, this feeling of being at home, sort of, hasn’t left me since.

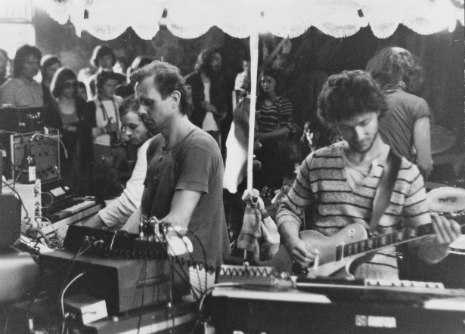

You know, I still live here. My studio was the Harmonia studio, where you see the three work spaces of Roedelius, Moebius and mine—I think it’s also in the book—you see the gear set up. That room is still my studio. Of course, it has changed; the gear has changed, and recently, since the arrival of the computer, that has significantly changed again, because I can work, I don’t know, I can work in a closet! [Laughs] All I need is a computer and a guitar, like I work live, you know. That setup which I carry around the world is what I basically need, and of course if I have some more gear, that’s also welcome.

I can’t part with Forst. I used to have a flat; my former partner, she let me use that flat in Hamburg when, in the wintertime, it gets rather dark and gloomy and muddy in Forst, but it’s different from city life, of course. In spring, summer, and also autumn, it’s beautiful. Today, I was up, I went into the toilet and I saw a beautiful sky with fog on the river, and I immediately grabbed my camera. I make photos all the time, because with each light—like daylight, bright sunshine, or dark atmosphere—you always have new impressions of the landscape.

Coming back to your question, apart from the beauty of the landscape, which really impressed me, of course, the thing was the lifestyle of the people and the lifestyle that was possible in this environment, which was, for me, a new experience. I came from Düsseldorf; I’d been living in cities with normal flats, and when I came to Forst, at the time—it’s really a funny anecdote—there was only one tap in the staircase with cold water. There was no sewage, nothing. There was just a pipe going through the wall, and everything went down just outside the house [laughs]. What I’m trying to say is, there was so much freedom to create your own living space, you know? Install heating, install proper sanitary things, and also, something I really enjoyed, I took a sledgehammer and just removed a wall that divided the space I could use, and just took out the wall to have a large room instead of two small ones. Try to do that in a flat in Düsseldorf! [Laughs]

So, the positive side was, we were really free. We could make music whenever we wanted to, nobody complained. We didn’t create much noise, but we had space, very much space to leave our gear. There were other people in Forst with whom we exchanged—like the people you see in the photos, you know, that was the kind of people, musicians came to visit. The basic thing is the freedom, really; it all comes down to the freedom.

The interview continues after the jump, plus the ONLY known footage of Harmonia, a Dangerous Minds exclusive!

1hfghgfh_465_349_int.jpg)

1hgngnghngn_465_349_int.jpg)