John Harvey Kellogg invented Corn Flakes as a means to stop masturbation. Kellogg believed a bowl of crispy morning goodness would stop youngsters from the evils of self-pollution, disease, and possible madness. Kellogg was a doctor, nutritionist, inventor, health freak, activist, and shrewd businessman. He wrote the treatise Plain Facts for Old and Young: Embracing the Natural History and Hygiene of Organic Life in which he cataloged a startling array of side-effects caused by the “doubly abominable” “crime” of onanism. His list included poor posture, stiffness of the joints, infirmity, bashfulness, and even an unhealthy predilection for spicy foods.

Kellogg believed diet played an enormous part in why so many youngsters wasted their lives in self-abuse. He, therefore, insisted on a diet of bland food, a cleansing of the bowels through regular use of enemas, and a daily bowl of his tasty Corn Flakes.

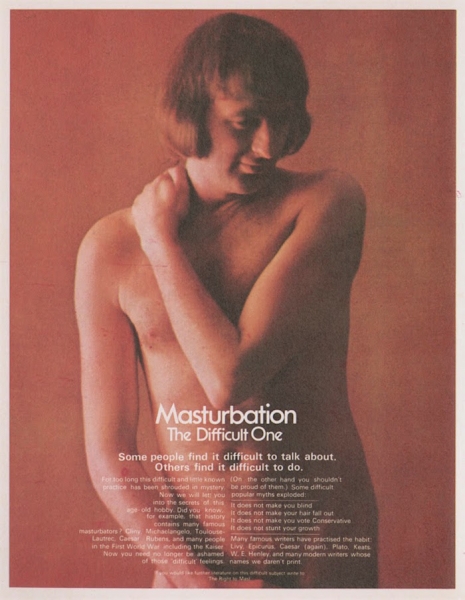

Masturbation was considered a very serious threat to the good health and clean-living of every young man and woman up as far up as the 1950s and even the 1960s. Some may recall Monty Python’s spoof advert in their Brand New Bok which displayed a naked Graham Chapman under the headline “Masturbation The Difficult One”:

Some people find it difficult to talk about. Others find it difficult to do.

The mock ad went on to explain how masturbation:

...does not make you blind

It does not make your hair fall out

It does not make you vote Conservative

It does not stunt your growth

Mr. Chapman and that difficult one.

The writer, lawyer, and “champagne socialist” John Mortimer, probably best known for his fictional character Rumpole of the Bailey, recounted in his autobiography Clinging to the Wreckage a tale of one of his classmates, a boy called Tainton, caught masturbating by the school chaplain, the suitably-named Mr. Percy.

Mr. Percy was deeply shocked to discover Tainton playing with himself and admonished him by saying:

“Really my boy, you should save that up till you are married.”

“Oh, I’m doing that, sir,” Tainton answered with his rare smile, “I’ve already got several jam jars full.”

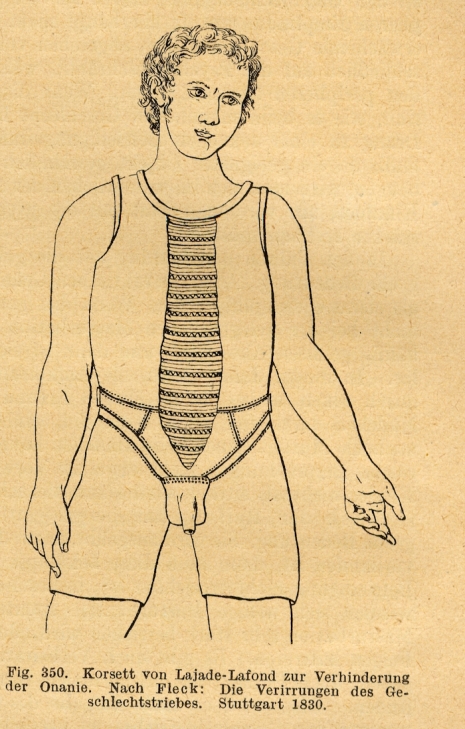

In a bid to stop such heinous behavior, various contraptions were invented to stop self-pollution. For young women, there was the chastity belt, and for men, well, a variety of painful devices including this one which was intended to lock the penis and testicles into a metal retainer to avoid any self-abuse.

This male chastity belt, or “surgical appliance,” was in use from the 1830s until the 1930s. The device may look like a novel fashion accessory or a variation on one of those “cock locks” favored by those into fetishism, cross-dressing, and a little S&M, but it was originally intended to put a stop to young men spilling their seed on stony ground, or rather in their hands or handkerchieves.

A male antimasturbation apparatus ca 1871-1930. According to the Science Museum:

This metal device is one of a number of similar devices which were invented in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries to prevent masturbation. A leather strap which would have kept it in place is now missing. Until the early 1900s, many people regarded masturbation as harmful to a person’s health, and it was blamed for a variety of ailments, including insanity.

More male anti-masturbation devices, after the jump…