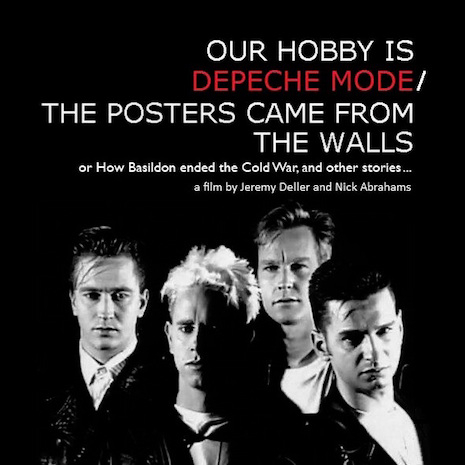

Sometimes things get lost because it’s easier that way. Like Jeremy Deller’s and Nicholas Abrahams’ 2007 documentary on Depeche Mode fans called Our Hobby is Depeche Mode (aka The Posters Came from the Walls). No one’s quite sure what happened there. Maybe it was accidentally filed under “F” for forgotten? Or perhaps carelessly pushed to the back of the archive where no-one would ever think to look except for maybe a very keen researcher hoping to find that one rare masterpiece for a festival schedule?

Who knows?

Whatever happened, happened. But very few people have seen Deller’s and Abrahams’ documentary, which to be frank is a goddamn shame.

Our Hobby is Depeche Mode is one of the best films ever made about music. It’s a staggering good documentary that has the audacity to speak to the fans and only the fans. Are you aware that Depeche Mode fans comprise one of the most ardent and hardcore fanbases of any group in the entire world history of popular music? Oh yes they do. Maybe not so much in their homeland England, but in many countries, Depeche Mode are viewed as actual heroes.

Jeremy Deller is a Turner Prize-winning artist and filmmaker. Nicholas Abrahams is a documentary filmmaker, artist and promo director. Their film Our Hobby is Depeche Mode documents the stories of Depeche Mode fans like Mark who was homeless when he found his love for the band. He slept rough under Hammersmith Bridge. His greatest fear was not finding food or comfort or money but would the batteries in his Walkman last so he had their music as company. Or, Masha, a girl in Russia who spends her time drawing intricate comic strips of her imaginary life with Depeche Mode. Or, Orlando who lights a candle every day at his shrine to the band. Or, the thousands of youngsters who gather every year in Moscow on Dave Gahan’s birthday to celebrate “Dave Day.”

I contacted Deller and Abrahams—the former over the phone, the latter over genteel refreshments in a busy Glasgow cafe—to find out about their documentary and what happened to it?

How did ‘Our Hobby is Depeche Mode’ come about?

Nicholas Abrahams: We were commissioned by Mute Records. They wanted to commission a film about Depeche Mode.

Jeremy Deller: They wanted a film to be made to celebrate some anniversary. They wanted a documentary about the band. We suggested this film about the fans and this way you don’t have to have the band involved.

NA: We pitched it as not about the band but what if it’s about the fans and how important the music can be to people in ways the band could never imagine. That was our pitch basically.

We knew if you made a film about the band, it maybe what a lot of Depeche Mode fans wanted but it’s boring people talking their music. We knew fans wouldn’t realise how interesting they are. And they were interesting.

JD: I was aware the band had this huge following in Eastern Europe and Russia. It was something I’d heard about but didn’t really know much about. I thought that would be quite fertile territory for the film.

NA: Daniel Miller [Head of Mute Records] knew Depeche Mode were huge in Russia but he didn’t know the story. He said, “It would be great to know about that.” We were discovering all that as we went along.

How did you find the fans for your film?

NA: We advertised through the official Depeche Mode website. Had any fans got stories about the effect the band had on their lives?

JD: I can’t remember how many we got but it must have been over 5,000 responses. We had to go through every one and work out if we could film these people, if it was worth filming them or not. It was kind of trial and error really. Some of them really stuck out, like Mark, because no one else really had a story like that.

It was trial and error and traveling around the world meeting people we’d never met before and filming an interview straight off, straight from the airport you go and make an interview and another one and another one. Then you’d have a night out with them. The next morning make an interview then go off on a plane. It was like being on tour.

NA: We were just looking for interesting people really. We also wanted to see the archive the fans had like the stuff from Russia the VHS tapes that were passed around like sacred objects and copied and re-copied.

JD: Depeche Mode for some people is a religion. In the same way, for us in Britain, the Beatles are like a religion. The effect is very similar to what the Beatles did to Britain and America in the 1960s.

I think it has enriched their lives, definitely. Maybe not financially but in terms of networks and friends and culturally. I think it has been good for people.

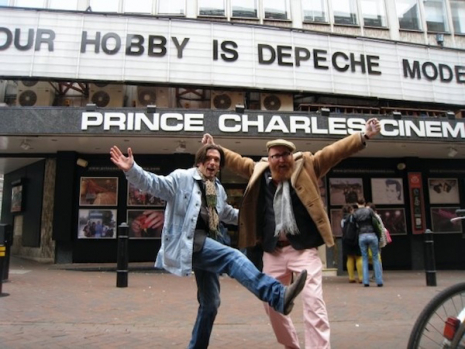

Deller and Abrahams.

Did you have any preconceived ideas about the kind of documentary you wanted to make before you started filming?

JD: You know what you want but you don’t know how you’re going to get to it. It’s so random really because you’re relying on the public. You can’t really control those people who you’re working with and filming. You know the kind of thing you want.

NA: We thought the stories in the film were culturally interesting, especially the stuff behind the Iron Curtain. At one stage it was going to be called How Basildon Ended the Cold War. Because it was like soft propaganda. And because in England they’re not taken that seriously where in other places they are. It’s as simple as that. Also how culture travels around the world, how it varies.

JD; A film with a global story which show’s [Depeche Mode’s] reach as a band really and how different countries look at them in different ways.

NA: It’s all tangential. None of this is what the band is aiming to do. People take something and use it in their own way. I suppose that’s part of what the film’s about.

We couldn’t have made the same film about another band, like say U2, because there’s an outsider-ish element to Depeche Mode.

Did you enjoy making it?

JD: I did actually. It was kind of amazing. It was quite tiring. I don’t know if I could make it now, you know, being a bit older. I think it would probably do my head in all the flying and stuff. Obviously there’s all that strain and stress when you don’t think you’re getting what you want and you’ve traveled all the way to a country and you can’t grab what you need and you know it’s there and you cannot find it. Those moments are potentially stressful.

What was the response from Mute Records and the band? And what happened to your film?

JD: Daniel Miller really loved it. But as soon as it got into the band camp or arena it sort of got lost a bit. We never really had any direct contact with them. We never really knew what they thought of it. It was made for them. It was paid for, ostensibly, by them. It sort of disappeared really.

NA: We were never asked to make changes. We just got shut down. It never got released.

JD: I think it got wrapped up in some band politics. Some politics within the organization which we weren’t really aware of and we had no control over. It just happens really. Bands are very strange things, they’re like little countries aren’t they? Especially bands that are very successful and make a lot of money. We were absorbed into that.

It’s never been put online and never been released as such—online or in cinemas or TV. We’ve never really exploited that. I think it’s time now that we can do it.

At this point, what are your hopes for ‘Our Hobby is Depeche Mode?

JD: I just want it to be seen really. It’s not as if I have some grand hope for it as it’s so old, if I’d made it last week i’d want everyone to see it. A lot of people have seen it. I just want it to be seen more widely really.

NA: It’s a total Valentine to the band.