This is a guest post by “undercover banker,” Em, an occasional contributor to Dangerous Minds. Born in NYC, he has lived all over the world. Em returned to the US in 2010 after working in London for 4 years. He’s currently making ready for Canada or France, just in case the lesser of evils does not prevail in November.

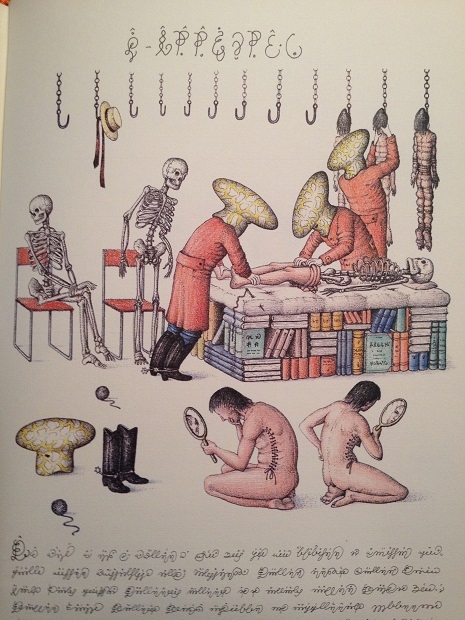

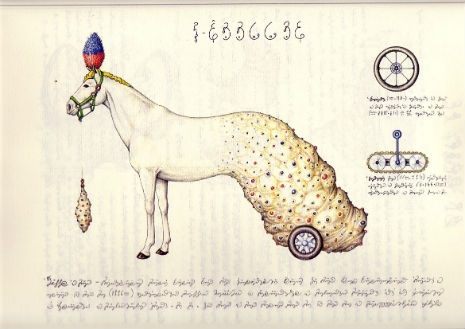

If you’ve been Dangerous Minds reader for a few years now, you might remember back in 2013, an article that I wrote—they tell me it’s one of the site’s most popular posts ever—about my decades-long search for what many people regard as the strangest book in the world, Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus. That book is both a figurative, as well as literal, encyclopedia of weirdness insofar as it describes in great detail the basic physics, flora and fauna, and even the vaguely human-like society of a world that doesn’t happen to exist. Well “describes” may be too strong a word as the entire volume is written in a language—and even a script—that no one to date has ever decoded.

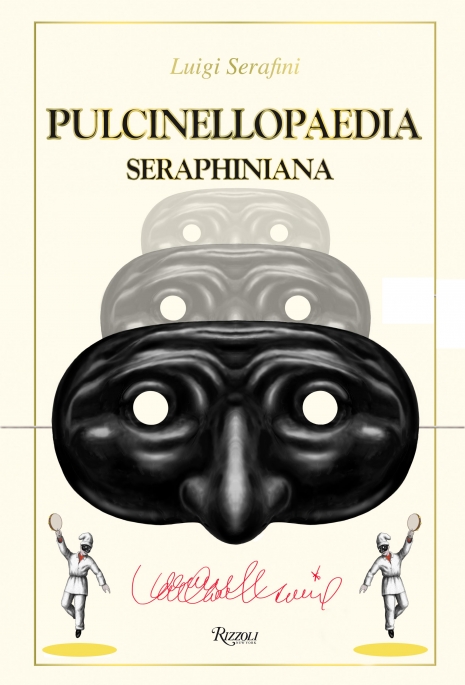

During my research on the Codex, I discovered that in 1984 Serafini created an even more obscure volume (if you can believe that) titled the Pulcinellopaedia Seraphiniana. Unlike the Codex, the Pulcinellopaedia Seraphiniana has never been republished until Rizzoli put out a new version (with new drawings) last week. There’s apparently both a standard hardcover as well as a signed, slipcased version, the latter limited to just 900 copies worldwide (300 in France, 300 in Italy and 300 in the US) and including a signed print.

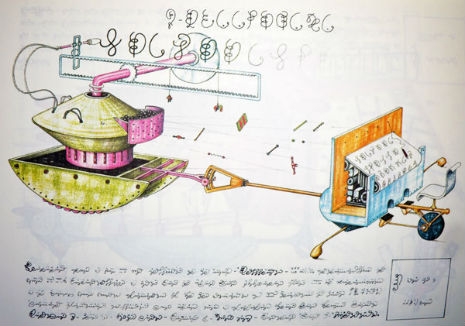

So, how does it compare, you might ask, to the infamous Codex Seraphinianus? Well, it’s similar insofar as there isn’t any text directly associated with the images or ideas therein, though there is a recent postscript (dated April 2016) describing in loose terms how the book originally came about (which Serafini discussed in more detail in my interview with him below.) And like the Codex this volume is filled with illustrations that defy category and some of which, when you take a second look, you could swear were not there before. (My explanation for that phenomenon is that some images just don’t map very well to anything in non-chemically-coaxed minds so that you forget some of them within minutes after you’ve turned the page.)

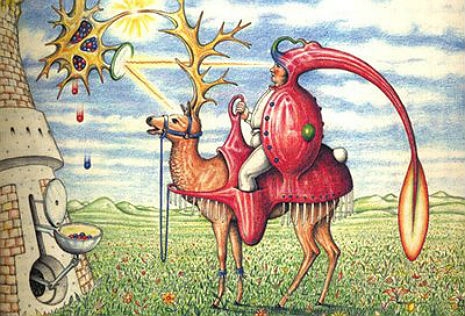

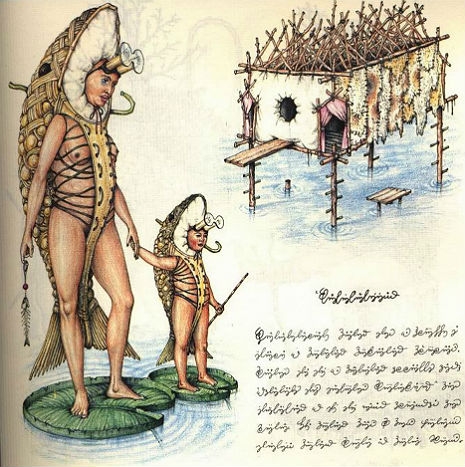

But that’s where the similarity with the Codex ends. Unlike the earlier book, the Pulcinellopaedia Seraphiniana kinda sorta has a narrative arc, as it appears to describe the coming of Pulcinella (aka “Punch” as he’s called in English) into the world, and the thousand-and-one things in the human realm that arise as a result of this classic trickster’s frolicking around in our collective unconscious (you know—it’s a Jungian thing). And Punch’s frolicking isn’t confined to puppets and plays and cute-but-slightly-annoying little tricks, but runs the gamut of human experience up to and including life and death. Who knows? Maybe even Donald Trump himself is a vast cosmic joke which some force beyond our ken is using to tempt us into self-annihilation, just for shits-and-giggles. Who can say from our lowly mortal perspective?

Visually the Pulcinellopaedia Seraphiniana is quite different from the Codex as well. First of all, the graphite images are rendered in a far more limited tonal palette, with black and white and some red making up the bulk of the colors. Second, the book is broken down into about ten sections that resemble movements in a musical piece, with each page usually containing a single image (though there’s a comics-like intro at the beginning that frames the rest of the book). This sets the pace and tone of the “narration” and kind of forces you to dwell on each image’s possible meaning before you turn the page. It’s a very different experience from “reading” the Codex and one where the physical medium of the paper book itself is put to essential use. Me, I love the thing and have been looking at it almost nonstop since they sent me the review copy (Do they expect to get this back? Well, they can’t have it ‘cause it’s, it’s… uh, lost…).

Did I mention I actually spoke to the mysterious Mr. Serafini over the phone at length a few days ago about the Pulcinellopaedia Seraphiniana? Well, I did. No, really. It was a wide-ranging and fascinating conversation that touched upon the history of Pulcinella and the Pulcinellopaedia and its origin in the Venetian Carnivale, masks, theater, Napoleon Bonaparte, Naples, Jungian psychology, Igor Stravinsky and even trickster modern artist Maurizio Cattelan. And let me state for the record that I truly believe that Serafini is both real (corporeal even) and not merely an incarnation of Pulcinella himself, despite the trickster-ish books he has created over the last several decades.

Here’s the heavily-edited interview, which was conducted in English

So Pulcinella spoke to you?

Luigi Serafini: Some people claim to have seen a ghost and nobody believes them. But then again I can say the same. I can say that I met Pulcinella…well obviously this was a fiction for my text, for my writing… but at the same time Pulcinella was a real part of the history Naples and indeed the first evidence of masks such as Pulcinella goes back to the second century A.D., or even before.

I didn’t know that.

Yes. The ancestor of Pulcinella was Macchus and the Atellan Farce in ancient Rome, and the character evolved over the centuries, finally appearing in its present form in approximately the 16th century in Commedia dell’arte. But an essential element was of course the mask, and only in recent times did actors perform on stage without masks.

It reminds me of the Carnivale in Venice. I guess all those people running around in masks are almost a holdover of something older that survived into modern times.

Well that’s very interesting because there is a connection between my book and the Carnivale of Venice. In 1982 I was invited to Venice because after two centuries the Carnivale started again, but very few people know this strange story. When Napoleon invaded Venice at the end of the 18th century, one of his first acts was to abolish the Venice Carnivale because all the masks were considered dangerous for the French army.

So the recent French prohibition of the niqab for Muslim women had a precedent?

Yes! And so after the Austrians came there was a treaty between Napoleon and Austria and they kept the same tradition of banning the Carnivale. So for two centuries there was no Carnivale… I mean in people’s houses they might celebrate, but in general there was no Carnivale for centuries in Venice in the sense we now know it. But in the late 70s, the director of the Biennale Theater thought that it was the time for a revival of the Carnivale. So after two centuries of no Carnivale at the end of it 1970s the Carnivale reappeared in Venice.

So in 1982 I was invited by in the city of Venice for this new Carnivale. It was a kind of a Carnivale which included a Napoli-type of carnivale and it was fate that I approached the Pulcinella mask. And I was fascinated by it so I built a huge mask of Pulcinella for the Carnivale and in the process I created so many drawings for the project that I had to make a book about Pulcinella and about what was bubbling up inside me. And at the same time it was kind of a challenge because after I did the Codex (the year before)—it was an incredible success for me. I mean I was completely surprised by it and everybody was waiting for some spinoff of the Codex and I said, no I want to do something completely different. While the Codex came more from my own conscious mind, the Pulcinellopaedia is based on what might be described in Jungian terms as coming from the collective unconscious, particularly as the character Pulcinella originates from the culture at large.

My feeling is that the Codex is about a different world than ours but the Pulcinellopaedia is about our world, except maybe showing these things that are happening behind the scenes.

Exactly. It’s the difference between the conscious and the collective unconscious—my unconscious in me is part of the collective unconscious which means it belongs to everybody while my fantasy belongs only to me. So there is something connected with Jung…

It almost looks like it has a story. But I can’t tell what the story is.

More than just a story it is a musical suite and like a suite in Western music it has separate pieces and separate movements that are tonally and semantically linked.

You mentioned Stravinsky’s Pulcinella piece in your book.

Yes. Exactly: It’s a work of mirrors. Now I referenced Stravinsky, Stravinsky referenced Pergolesi, Pergolesi looked at Naples because he worked in Naples. Everybody reflects something from a mirror to somebody else, etcetera etcetera… So it’s a game. It’s a mirror game to me. Stravinsky. Pergolesi. Naples. Masks, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.

Can you give us any clues as to how to understand the Pulcinellopaedia? Like what’s with the spaghetti? The Pulcinella character is often interacting with spaghetti.

Okay, to more deeply understand the Pulcinellopaedia, the best way is a seven day trip to Naples. So you go out there and you enjoy the lifestyle and the beauty of this very particular city which is dominated by the volcano Mt. Vesuvius. So you always have this image of life and death because of the volcano, the eruption and Pompeii as if everything is just on the border between life and death. So Pulcinella could only be formed there, you know, and he frames and represents the joy of life and naturally, food is an important part of our life. So at the same time spaghetti illustrates the poverty of Pulcinella and his genius to survive, even if he is poor. So his genius is using all the tricks of fantasy like this to find a kind of inner peace in life.

That makes sense. I think at some point in the book Pulcinella looks like he breaks into two, maybe you know, kind of a life one and a death one and they seem to be fighting, I guess, constantly, kind of a balance between the two that’s never fully resolved.

Pulcinella is strange because it seems that whatever he does he always makes another Pulcinella or some sort of image or reflection of him emerges. So in that he is unique and at the same time he’s lonely and like an actor, in the end it’s the theater actor who is close to the audience. The theater is really a serious place where loneliness and the audience meet. And so the actor assumes the problems of the collective unconscious. And at the same time at the end of the performance they’re alone and afterwards he goes back into normal life.

Even in a movie theater you’ve got hundreds of people there gathered in the dark who don’t know each other. And they are all sitting together watching the same show…

So I noticed at the end of the book it looks like you have newer drawings.

LS: Yeah. Because I drew Batman and Superman. Batman for me is a heritage of the Commedia dell’arte and the superheroes are masked people like in the Commedia dell’arte. And so they’re really specializing in something. And it may be that the heritage of Commedia dell’arte is in comics right now. This is where we can see all the masked people which embody some virtues or vices—both—of ourselves.

Continues after the jump…