1966: Francis Ford Coppola was working as a scriptwriter when he had a conversation with director Irvin Kershner about spy movies. Espionage films were big bucks in the mid-sixties with the unequaled success of the James Bond franchise, the escalation of the so-called Cold War between the West and Soviet Russia, and the NY Times best-seller list filled with spy stories like The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, The IPCRESS File and A Dandy in Aspic.

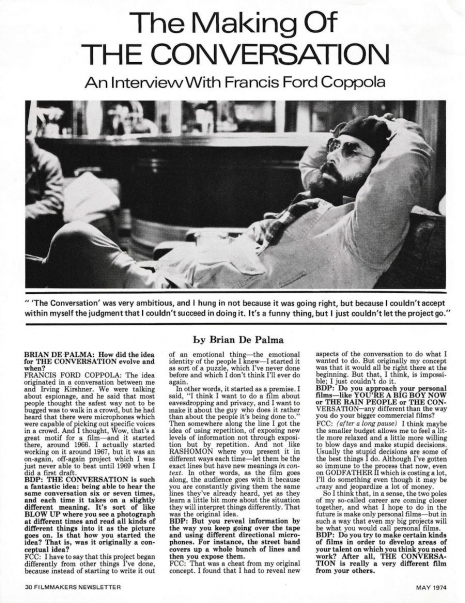

Kershner was making A Fine Madness with Bond star Sean Connery. Coppola was learning his trade writing screenplays like This Property Is Condemned and Is Paris Burning?. As he later recounted in an interview with Brian De Palma for the magazine Filmmakers Newsletter in 1974, his chat with Kershner was the moment he first had the idea to write The Conversation:

We were talking about espionage, and he said that most people thought the safest way not to be bugged was to walk in a crowd. And I thought, Wow, that’s a great motif for a film—and it started there, around 1966. I actually started working on it around 1967, but it was an on-again, off-again project which I was just never able to beat until 1969 when I did the first draft.

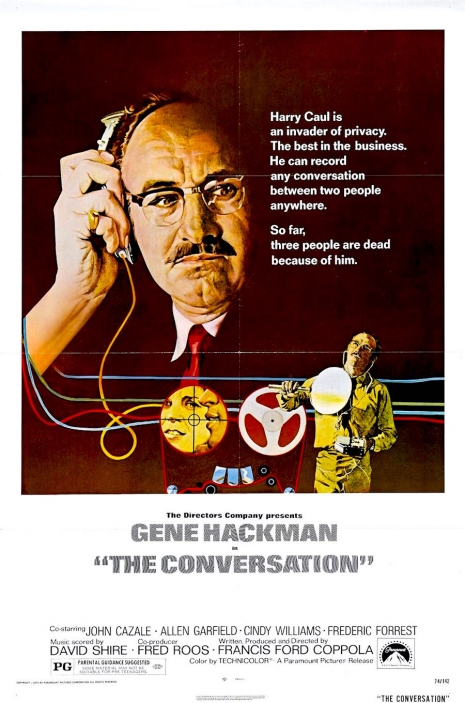

The Conversation follows surveillance expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) who is hired to monitor a young couple. From his covert recordings Caul thinks he may have uncovered a possible murder as the couple’s recorded dialog includes the phrase “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” Caul plays and replays the tape in his obsessive and paranoid attempt to decipher the dialog’s real meaning.

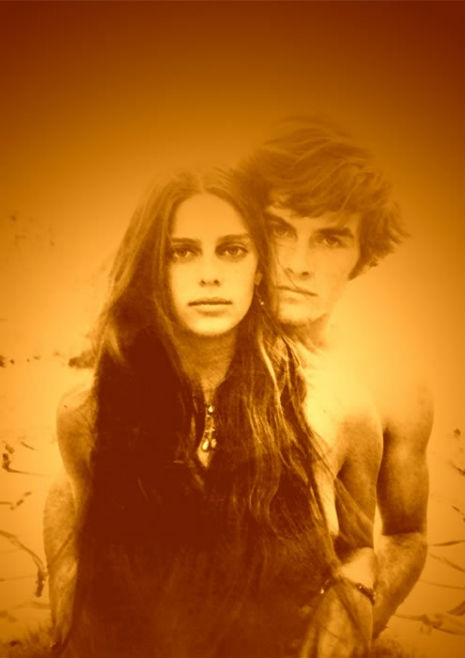

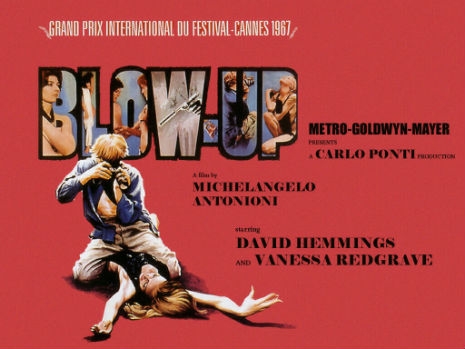

Coppola was influenced by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) which used a similar plot device—in this case a young photographer (David Hemmings) thinks he may have captured evidence of a murder with his camera.

I got into THE CONVERSATION because I was reading [Hermann] Hesse and saw BLOW-UP at the same time. And I’m very open about its relevance to THE CONVERSATION because I think the two films are actually very different. What’s similar about them is obviously similar, and that’s where it ends. But it was my admiration for the moods and the way those things happened in that film which made me say, “I want to do something like that.”

Every young director goes through that.

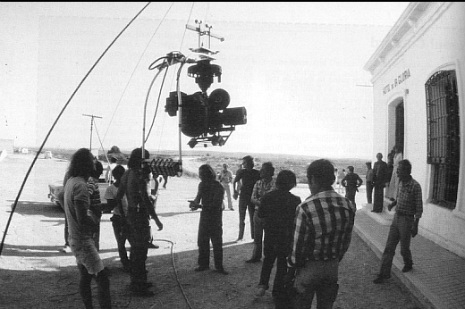

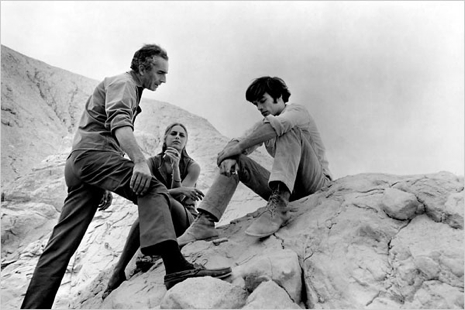

Coppola and Hackman on location during filming for ‘The Conversation’ in 1973.

Coppola didn’t want to make a rehash of Blow-Up or a token movie version of Hesse’s cult novel Steppenwolf—though he did take some inspiration from the book’s central character Harry Haller—“a middle European who lives alone in a rooming house”—and his delusional fantasies. (The book also contains a significant role played by a saxophonist.) Coppola was more interested in approaching his script as a puzzle:

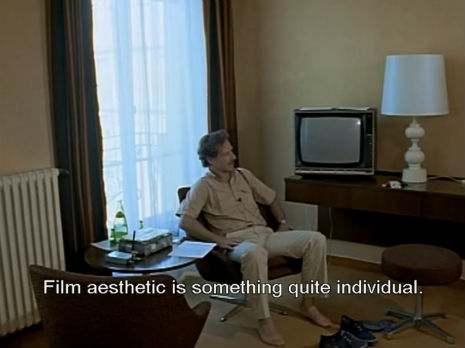

I have to say [The Conversation] began differently form other things I’ve done, because instead of stating to write it out of an emotional thing—the emotional identity of the people I knew—I started it as sort of a puzzle, which I’ve never done before and which I don’t think I’ll ever do again.

In other words, it started as a premise. I said, “I think I want to do a film about eavesdropping and privacy, and I want to make it about the guy who does it rather than about the people it’s being done to.” Then somewhere along the line I got the idea of using repetition, of exposing new levels of information not through exposition but by repetition. And not like RASHOMON where you present it in different ways each time—let them be the exact lines but have new meanings in context.

In other words, as the film goes along, the audience goes with it because you are constantly giving them the same lines they’ve already heard, yet as they learn a little bit more about the situation they will interpret things differently. That was the original idea.

De Palma is a good interviewer. He gets Coppola to open up on his filmmaking technique where many other interviewers may have failed. The whole interview was published (including a few spelling mistakes) in the seminal magazine Filmmakers Newsletter in May 1974 and has been uploaded by Cinephilia and Beyond. Click on the images below to read the whole conversation between De Palma and Coppola.

Read the whole interview between De Palma and Coppola, after the jump…