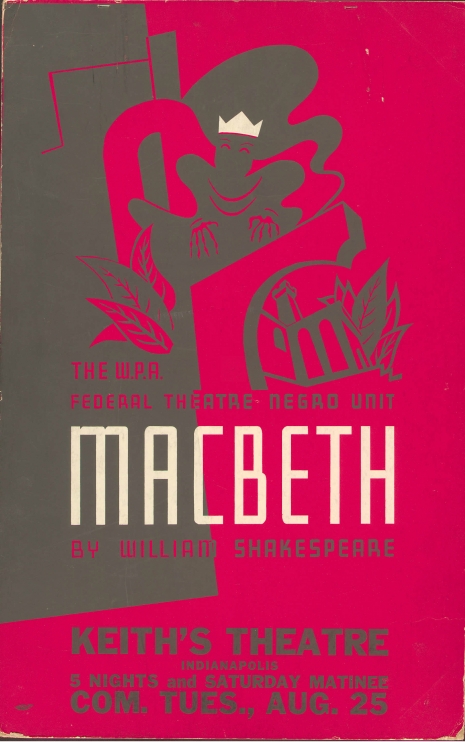

Poster for the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth on tour in Indianapolis (WPA Federal Theatre Photos, via Library of Congress)

A theater company in St. Petersburg, Florida recently mounted a revival of Orson Welles’ “Voodoo” Macbeth, which transposed the medieval violence and witchcraft of Shakespeare’s “Scottish play” into 19th century Haiti. The show and the stir it caused had much to do with the Welles legend. When it opened at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre on April 14, 1936, some 10,000 people surrounded the venue, blocking traffic on Seventh Avenue; when the show toured the country after a three-month run in Harlem, the playbill boasted that the original engagement played to 150,000 people.

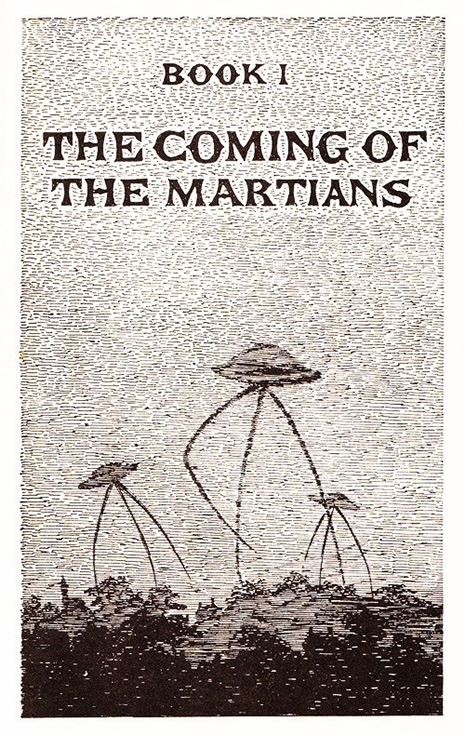

The original production was financed by the New Deal. During the second half of the thirties, the Federal Theatre Project funded performances to feed starving actors and keep stages open. One of these was the Negro Theatre Unit’s Macbeth, directed by a 20-year-old Orson Welles. Despite his youth, Welles was not timid around the Bard, having published a three-volume set of Shakespeare plays “edited for reading and arranged for staging” during his teens. Among other revisions and inventions (such as the unmistakably Wellesian costumes and sets), Welles’ audacious staging of Macbeth replaced the three witches with a troupe of Voodoo drummers and dancers.

WPA Federal Theatre Photos, via Detroit Public Library

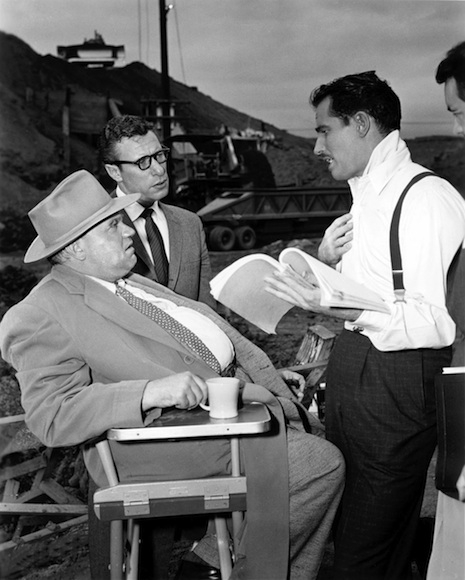

There is a wonderful story about the theater critic Percy Hammond, who panned the show in the New York Herald Tribune and died shortly thereafter. The tale exists in many versions; here’s how John Houseman, Welles’ friend and mentor, who was in charge of the Negro Theatre Unit and brought Welles on board, tells it in Voices from the Federal Theatre:

When we did the Voodoo Macbeth, it was very successful, and we got very nice reviews except from a few die-hard Republican papers. Percy Hammond wrote a perfectly awful review saying this was a disgrace that money was being spent on these people who couldn’t even speak English and didn’t know how to do anything. It was a dreadful review but purely a political review.

We had in the cast of Macbeth about twelve voodoo drummers and one magic man, a medicine man who used to have convulsions on the stage every night. They decided that this was a very evil act by Mr. Hammond, and they came to Orson and me and showed the review. They say, “This is bad man.” And we said, “Yeah, a helluva bad man. Sure, he’s a bad man.”

The next day when Orson and I came to the theatre, the theatre manager said, “I don’t know how to tell you this, but there were some very strange goings-on last night. After the show they stayed in the theatre, and there was drumming and chanting and stuff.” We said, “Oh, really?” What made it interesting was the fact that we’d just read the afternoon papers. Percy Hammond had just been taken to the hospital with an acute attack of something from which he died a few days later. We always were convinced that we had unwittingly killed him.

WPA Federal Theatre Photos, via Detroit Public Library

Jean Cocteau, who was then reenacting Phileas Fogg’s circumnavigation of the planet, caught the “Voodoo” Macbeth in Harlem. Welles’ biographer Simon Callow reports that Cocteau, though put off at first by the startling changes in lighting, came to appreciate its “Wagnerian” effect, which heightened the play’s violence. In Cocteau’s account of his travels, Mon Premier Voyage, after recording a few criticisms of Welles’ choices, he expresses his admiration for the show:

But these are details. At the La Fayette theatre that sublime drama is played as nowhere else, and in its black fires the final scene is transmuted into a gorgeous ballet of catastrophe and death.

WPA Federal Theatre Photos, via Detroit Public Library

WPA Federal Theatre Photos, via Detroit Public Library

Thanks to another New Deal program, the Works Progress Administration, some film of the original “Voodoo” Macbeth survives. We Work Again, the WPA’s documentary on African American unemployment, culminates in this footage of the production, touted by the narrator in the old-fashioned American rhetorical style:

The Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project produced a highly successful version of Shakespeare’s immortal tragedy Macbeth, which far exceeded its scheduled run in New York and was later sent on a tour of the country. The scene was changed from Scotland to Haiti, but the spirit of Macbeth and every line in the play has remained intact. In this contribution to the American theatre, and in other projects under the Works program, we have set our feet on the road to a brighter future.

More after the jump…