Jonathan Miller first considered the possibility of making a film of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland during a party in the early 1960s. Miller was discussing the book, over the percussive clink of ice cubes on glass and the tidal rise and fall from excited chattering voices, with the playwright Lillian Hellman. Miller explained that although Carroll’s book had been filmed before it had never been done properly. These previous efforts, he claimed, had been “too jokey, or else too literal..and…had always come unstuck by trying to recreate the style of Tenniel’s original illustrations.” Copying Tenniel might work in animation but never, oh never on film.

Miller considered Alice in Wonderland “an inward sort of work, more of a mood than a story.” Before he could turn it into a film he wanted to make, he had to discover “some new key” with which to unlock the book’s hidden feeling. To find the possible answer, Miller asked:

What was Charles Dodgson (alias Lewis Carroll) about?

and:

What is the strange secret command of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)?

His answer, as he explained in article for Vogue, December 1966: “Nostalgia and remorse.”

Like so many Victorians, Dodgson was hung up on the romantic agony of childhood. The Victorians looked on infancy as a period of perilous wonder, when the world was experienced with such keen intensity that growing up seemed like a fail and a betrayal. And yet they seemed to do everything they could to smother this primal intensity of childhood. Instead of listening to these witnesses of innocence, they silenced them, taught them elaborate manners, and reminded them of their bounded duty to be seen and not heard.

Lewis Carroll’s novels about Alice in a magical wonderland were books “about the pains of growing up.”

Everyone Alice meets on the way…represents one of the different penalties of growing up. One after the other, the characters seem to be punished or pained by their maturity.

Cor blimey! The wonderful Mr. Miller had an incredible intellect, a polymath, an immensely talented polymath who seemed to want to rationalise everything he encountered. But often, perhaps too often, in doing so, the dear old doctor took some of the magic away. I greatly admired Jonathan Miller, he was one of my childhood heroes, but I am willing to believe in the rhinoceros under the table (or the elephant in the room) as much as there ever so might just be fairies at the bottom of the garden—as G. K. Chesterton (jokingly) believed. Or, as the great comedian Eric Morecambe once joked about religion: Two goldfish swimming in a goldfish bowl. One said to the other, “Do you believe in God?” “No, of course not. Why?” “Well,” the first replied, “Who changes the water?”

It’s all about perspective.

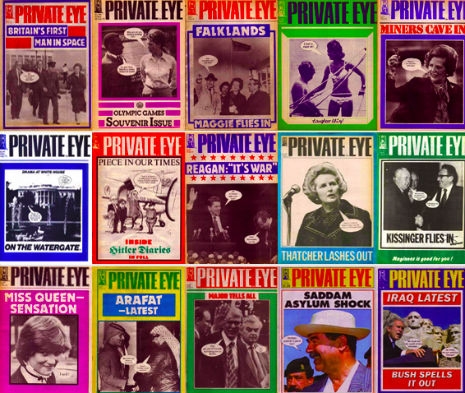

Miller cut Carroll’s artifice of wonderfully exotic creatures (the White Rabbit, the Gryphon, the Caterpillar, and so on) and turned them into the academics he believed they were based on. A startlingly brilliant idea at a point in history when everyone was supposedly questioning everything about the Establishment and the old tenets of Queen and Country, religion and class—all of which were (rightly) under attack. As Miller noted:

The animal heads and playing cards are just camouflage. All the characters in the book are real, and the papier-mache disguises with which Carroll covers them all up do nothing to hide the indolent despair.

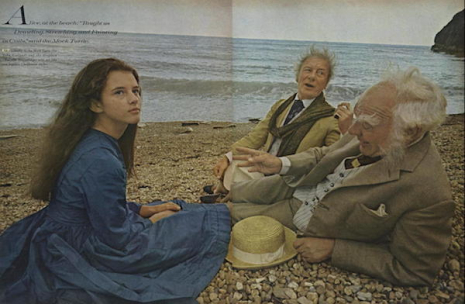

Once this was clear, the way to make the film fell neatly into place. No snouts, no whiskers, no carnival masks. Everyone could be just as he was. And Alice herself? Not the pretty sweetling of popular fancy. I advertised fro a solemn, sallow child, priggish and curiously plain. I knew exactly what she would be like when I found her. Still, haughty and indifferent, with a high smooth brow, long neck and a great head of Sphinx hair.

Apparently, seven hundred children applied, or at least their parents did, but Miller did not interview any of them, until he chanced upon a photograph of Anne-Marie Mallick, “a dignified schoolgirl of Indian-French stock with a mane of dark hair.” Who, as Miller’s biographer Kate Bassett notes, represented an Alice who “was exclusively a child of the director’s era, manifesting the auteur’s (rather than the original author’s) divided personality and ambivalence towards authority figures.”

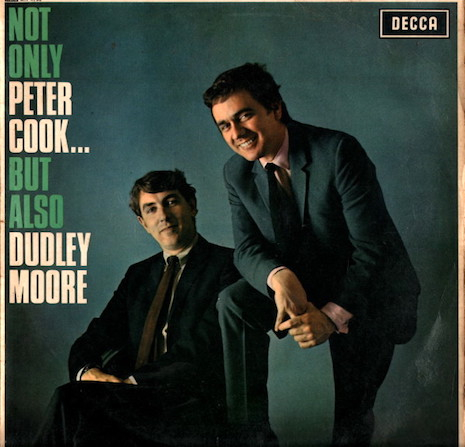

The former co-star of Beyond the Fringe, recognised Carroll’s satire as “amusing youngsters by sending up old, sententious types” which “tallied with the spirit of the 1960s.”

Thus the perceptive viewer of the film was able to see double: the two decades translucently overlaid, though a century apart, as if it were a pleat in time.

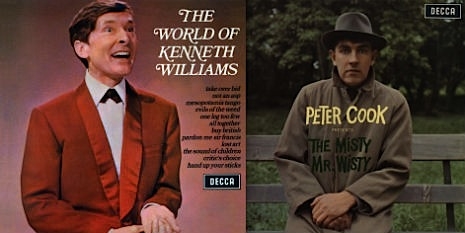

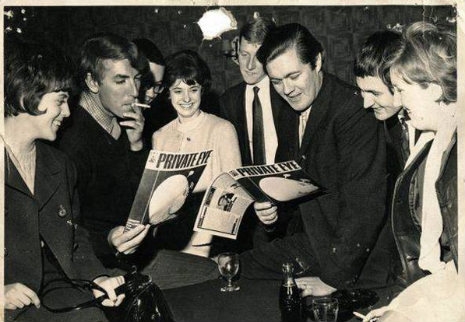

Made for BBC Television, Alice in Wonderland was filmed over nine weeks in a dreamy English summer. Miller created a masterpiece of television and film—which was as much influenced by Orson Welles’ The Trial as it was by Ken Russell’s The Debussy Film or Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Saint Matthew. All of which Miller acknowledged. Miller wrote the screenplay, and did collect one of the best casts imaginable including Peter Sellers, Peter Cook, John Gielgud, Michael Redgrave. Alan Bennett, and Leo McKern, amongst others, all for a flat fee of £500 each. And the music score by Ravi Shankar is highly effective.

Watch the rest of Miller’s ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ after the jump…