Jean Delville’s title page for ‘Prometheus’

I’m no synesthete, so I’m still not sure what Eddie Van Halen meant by “the brown sound.” Sorry, Eddie: I’m the kind of literal-minded philistine who sees with his eyes and hears with his ears. Regular slobs like me have to make do with the pitch-and-color correspondences of Alexander Scriabin’s Theosophically inspired score Prometheus: Poem of Fire, which included a part for color organ.

(N.B.: As this article points out, a century ago, “synesthesia” did not exclusively refer to a neurological condition, but described “a broad range of cross-sensory phenomena” that could arise from mystical or aesthetic experience. So asking whether Scriabin himself was “really” a synesthete is beside the point.)

There’s ever so much bullshit about Prometheus on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Internet. As a corrective, let’s start with some heavy scholarship from the eminent musicologist Nicolas Slonimsky:

Scriabin made an earnest attempt to combine light and sound in the score of Prometheus, in which he includes a special part, Luce, symbolizing the fire that Prometheus stole from the gods. It is notated on the musical staff as a clavier à lumieres, a color organ intended to flood the concert hall in a kaleidoscope of changing lights, corresponding to the changing harmonies of the music. Unfortunately, the task of constructing such a color keyboard was beyond the technical capacities of Scriabin’s time. Serge Koussevitzky, the great champion of Scriabin’s music, had to omit the Luce part at the world première of Prometheus which he conducted in Moscow in 1911.

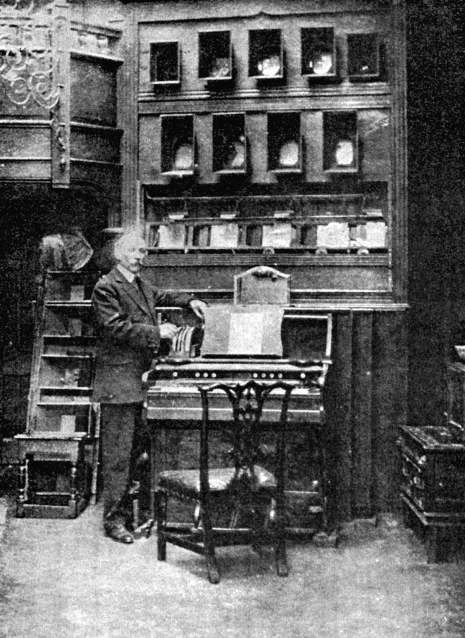

Alexander Wallace Rimington with Colour-Organ (an instrument that did not, in fact, perform ‘Prometheus’ in 1915)

The Russian Symphony Society gave the first performance of Prometheus with lights at Carnegie Hall on March 20, 1915, a little over a month before the composer’s death. James M. Baker’s “Prometheus and the Quest for Color-Music” sets Scriabin’s work in historical context and traces its path to Seventh Avenue. The essay overflows with detail on the particular system of correspondences Scriabin worked out, the history of synesthetic compositions, and Prometheus’ relationship to Theosophical lore. Significantly, Baker agrees with Slonimsky that, when Scriabin wrote Prometheus, he had no clue how the Luce portion of the score would actually be played (much less how “to flood the concert hall” with colors):

Although documents from the time are sprinkled with comments hinting that various color apparatuses had been tried and had failed in preparing earlier performances, in actuality there was no color organ ready and available for which Scriabin had conceived the part. It is true that Alexander Mozer, the composer’s friend and disciple who taught electrical engineering at a Moscow technical school, had constructed a small color device with which Scriabin experimented in his apartment, but this was merely a crude circle of colored light bulbs mounted on a wooden base.

Alexander Mozer’s ‘small color device’ at the Scriabin Museum in Moscow

Baker writes that Scriabin’s plans for English performances of Prometheus accompanied by A. Wallace Rimington’s color organ were scotched by the outbreak of World War I. In New York, the technical problem fell to the Edison Testing Laboratories, which invented a color organ especially for the show: the Chromola, a keyboard of 15 keys hooked up to a number of lamps behind color filters, with two pedals to control their intensity. While more impressive than Mozer’s “crude circle of colored light bulbs,” the projections on a gauze screen fell short of the composer’s desired effect. The May 1915 issue of The Edison Monthly represented the debut performance of Scriabin’s “special light score” as a modest success:

The theory of the production is roughly this: Following out the analogy of light and sound vibration, Scriabine [sic], the Russian composer, hit upon the notion of writing a color score to accompany his orchestral “Poem of Fire.” In theory, the audience was to sit bathed in floods of changing light whose variations in tint and intensity should follow the sound variations. In practice, however, this became more complex.

It was found impossible to achieve “floods of light,” and in their place a gauze screen was provided on which the changing hues were thrown, controlled from a cleverly designed “color organ” or “chromola.” Scriabine’s original color scale was found defective and a more scientific one was provided, based on rate of vibrations, each octave extending from deep red at one end of the spectrum to violet at the other. Thus pitch was made analogous to hue, loudness to shade and quality to the intensity of illumination. Advocates of mobile color feel sufficiently encouraged by their experiment to wish to attempt another production under more favorable conditions. And apparently one of these will be a score somewhat less bewilderingly dissonant than the “Poem of Fire.”

Below, a 2010 performance of Prometheus approximates the totally bitchin’ immersive light show Scriabin imagined, with the help of 21st century lighting tech and Yale’s massive endowment (that’s Ivy League coin, perv!).