‘The Three Million Case’ (1926).

The brothers Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg were two engineers who became famous as the artists and designers of some of Soviet Russia’s greatest movie posters during the 1920s. Together, the brothers produced hundreds of posters many of which have been sadly lost as they were intended to be used only once. Cinema was considered a key propaganda tool—a bit like the Internet is today—for keeping the largely illiterate union of socialist Soviet peoples on target for building the dream of a “New Worker’s Paradise.”

The brothers were the children of a Russian mother and a Swedish father. They kept their Swedish nationality until 1933 when they were forced to sign-up as Russian citizens. This was the same year Vladimir died in an automobile accident. Georgii continued to work as a designer and was responsible for organizing the displays on Red Square for the May Day celebrations of 1947. Their once ground-breaking and avant-garde style had become part of the established order.

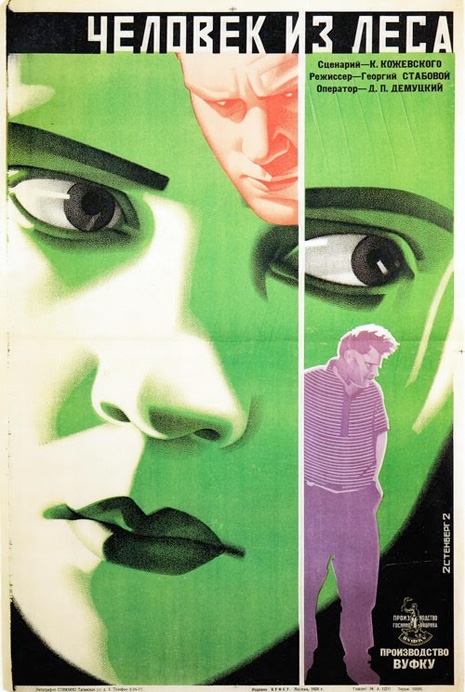

Their background in engineering gave the pair an edge over other their designer rivals/comrades who still favored painting for their poster work. The brothers were greatly influenced by Constructivism and Dada, which inspired their use of montage, typography, and visual distortion in their work. They were involved in setting up a society for young artists, produced some of the posters issued for the May Day celebrations in 1918, and even exhibited artwork in Berlin. Yet, it was their movie posters which have had the longest and most far-reaching influence and subsequent generations and designers across the world.

Most of the following is the work of the brothers Stenberg—the exceptions being their collaboration with Yakov Ruklevsy (The Decembrists and October), Viktor Klimashin (The Death of Sensation) and Oil which is solely by Aleksandr Naumov. As a sidebar, these posters might all look dynamic and utterly thrilling but sometimes they are selling documentaries and training films—take for example the beautifully film noirsh treatment for a documentary on Cement.

‘Countess Shirvanskaya’ (1926).

‘The Screw from Another Machine’ (1926).

More revolutionary posters, after the jump…