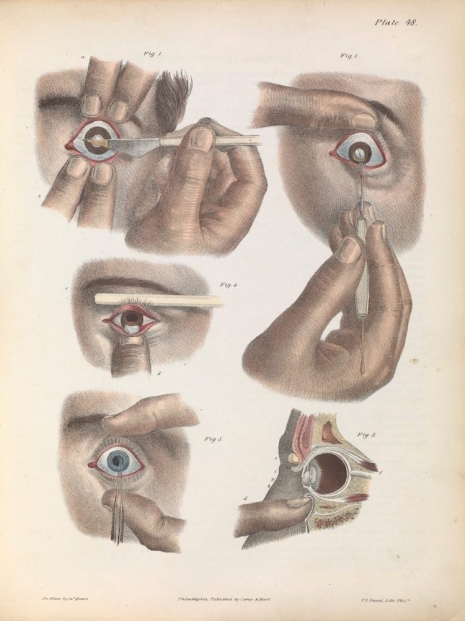

Surgery to correct strabismus, a misalignment of the eyes.

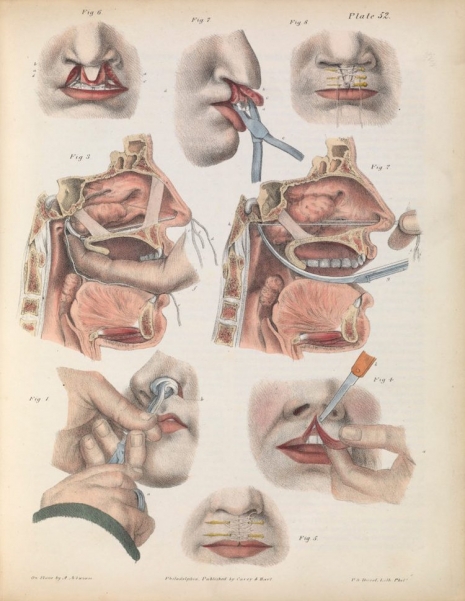

The artist Francis Bacon spent many hours poring over illustrated medical books looking at surgical procedures on mouth and tongue cancer, hare-lip correction, and tracheotomies. He declared these image beautiful, in particular the way in which the artist had used color to represent a tongue or a mouth. It was something he tried to recreate in his own paintings. Bacon was a voracious reader. After his death, more than 1,000 of his books were donated to Dublin’s Trinity College History of Art Department and the City Gallery, the Hugh Lane. Among this collection are works by Beckett, Nietzsche, T. S. Eliot, De Beauvoir, Elizabeth David cookery books, and a well-used set of medical textbooks, some illustrated by Frank Netter, others containing work by Joseph Pancoast (1805-82).

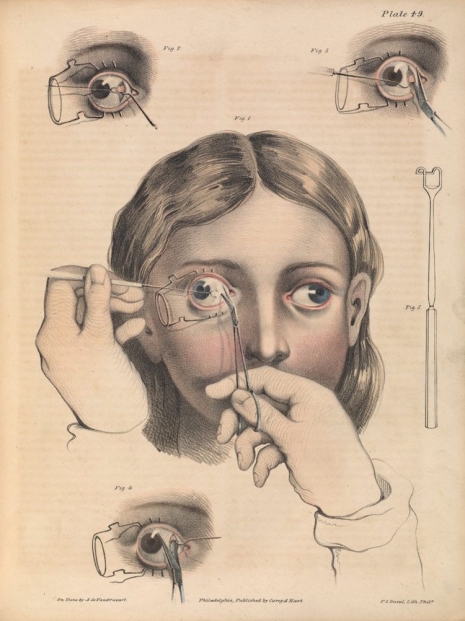

Pancoast was an American surgeon who pioneered many techniques in surgery and in particular plastic surgery. He also wrote the highly influential book A Treatise on Operative Surgery, first published in 1844, which compiled various surgical procedures or “processes” that exhibited the “state of surgical science in is present advanced condition.” The book contained some 80 color-plates and 486 illustrations, and was further enlarged in 1846.

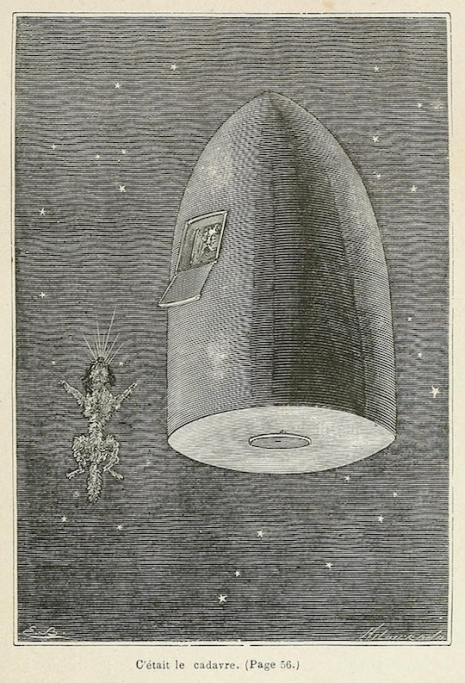

Illustrations from another medical book that caught Bacon’s interest was Précis iconographique de médecine opératoire et d’anatomie chirurgicale by Claude Bernard (1813-1878), a French physiologist, who has been described as “one of the greatest of all men of science.” Bernard was the first to use “blind experiments” by which information is kept from the participants to eliminate any possible bias. He also believed scientists must endeavor to disprove their own theories as scientists can “solidly settle” their ideas “only by trying to destroy [their] own conclusions by counter-experiments.”

Like Bacon, I’ve had a long fascination with old medical textbooks and their illustrations as I find the artists’ depictions of surgery and disease beautifully capture the essential frailty of the human condition. However, some readers may find a few of the following illustrations potentially disturbing. You have been warned.

The removal of cataracts.

Surgery for correcting a harelip.

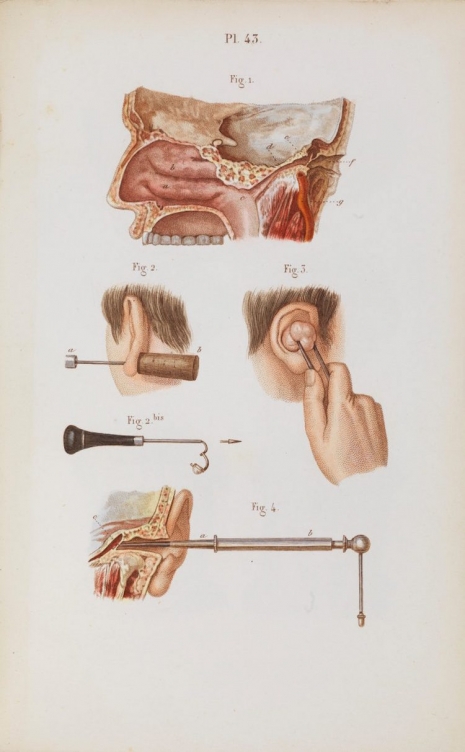

Ear surgery.

Far more disturbing surgical procedures, after the jump….